Filed under: war-machine | Tags: active, bay of rage, debord, guy debord, la riots, oakland, passive, police, research and destroy, rodney king, spectacle, violence

From Bayofrage:

ϕ

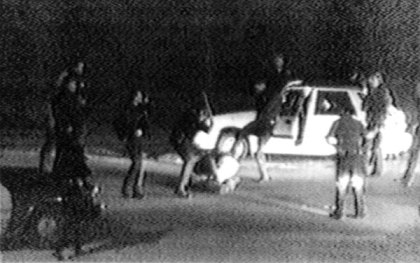

LOS ANGELES, March 3, 1991 – On the shoulder of the freeway, police are beating a man. Because we are in the US, and because the man is black, we will know that this is a routine event, an ordinary brutality, part of the very fabric of everyday life for non-whites. But something is exceptional this time. There is an observer, as there often is, but the observer holds in his hands an inhuman witness, a little device for producing images which are accepted as identical with the real. The images – grainy, shaking with the traces of the body behind them – enframe this event, defamiliarize it, make it appear in all its awfulness as both unimaginable singularity and example of a broader category of everyday violence. The recorded beating of Rodney King marks, as many have noted, the beginning of one of the most significant episodes of US history. But few have examined this event in terms of the transformative effects it exerted upon contemporary spectacle and its would-be enemies. By spectacle, we mean here those social relations and activities which are mediated directly by the representations, whether visual or verbal, which capital has subsumed (that is, remade according to its own imperatives).

For us, the advent of the Rodney King video marks the first major shift in the political economy of spectacle, which we choose to describe as a passage from passive to active spectacle, from spectacle as pacifying object of passive consumption to spectacle as the active product of the consumer (whose leisures or recreations have long since become forms of work). In its classical form, spectacle creates a situation in which “spectators are linked solely by their one-way relationship to the very center that keeps them isolated from each other” (Debord.) But at a certain point in its development, spectacle dispenses with the need for centralization, finding that passive consumers can quite easily be recruited to the production of spectacle. The shift from unilateral toward multilateral relations does not promise an end to isolation, but rather its perfection. We might think of the distinction here as the difference between the television screen and the computer screen, but since we are talking about a set of social relations as much as technological apparatuses, we should be careful to avoid identifying such relations with any particular technologies. The video camera is merely one of many devices which assist in the transformation of administered life into self-administered life.

But back to the origin story (like all origin stories, it’s partly myth). The mutation from passive to active spectacle begins, as seems properly literary, square in the middle of one of the most significant nerve-plexuses of the spectacular world: Rodney King is beaten to the edge of death a few miles from the studios of Burbank and Hollywood, while celebrities whizz by in Porsches and Maseratis. A routine event, an ordinary brutality, an everyday violence: a black man is pulled over by white police officers. They have some reason or another. There is always a reason, if only raison d’État. They beat King savagely, until he is almost dead. Perhaps they have gone a little too far this time, gotten a little overexcited? In any case, it’s nothing that can’t be taken care of, made to disappear with a few obfuscatory phrases in the police report. Except that, somehow, everything is different here. Recorded, duplicated, transmitted, broken down into the pixels of a million television screens, the video tape is more than evidence. It is self-evidence. And because these images are drained of all affect, reduced to pure objectivity, they can become the vehicle for the most violent and intense of affects.

ϕ

The release of this video marks, more or less, the entrance into history of the video camera as weapon, as instrument of counter-surveillance. For a brief moment it does seem, for many, as if the truth really will set us free. As if the problem with capitalism was that people just didn’t know, just didn’t understand, just hadn’t seen what it’s really like underneath the ideological mist. Noam Chomsky’s politics as much as Julian Assange’s seem to hinge upon this kind of moment – so rare, really – when the release of information becomes explosive, as opposed to the thousands of other moments when the leaked photographs of government torture camps or the public records dump indicating widespread fraud and corruption fail to elicit any outrage whatsoever. From here and from the related forms of media activism which the Rodney King tape precipitates, there flows an entire politics of transparency, based on a correlation between the free circulation of information and freedom as such, which we will recognize as the politics of Wikileaks and the more-libertarian wing of Anonymous. But this is also the matrix from which emerges the ideology of the Twitter hashtag and the livestreamed video that so animates the Occupy movement and the 15 May movement in Spain, an ideology that seems incapable of distinguishing between OWS and #ows, between the massification of “tweets” around a particular theme and the massing of bodies together in an occupied square. As many of us will know from the experience of the last year, this is an ideology that speaks of democracy but reeks of surveillance, whose wish for a world transparent to all means that it sees a provocateur behind every masked face and unassailable virtue in all that is visible and unmasked.

ϕ

But we have already skipped to the end, it seems, far from the infancy of active spectacle. At first, it’s true, the mass media display a certain hostility to these newer “participatory” forms of media distribution and production, which seem to threaten the centralized, unidirectional spectacle upon which the mass media are built. The various conglomerates even resort to outright repression on occasion. But from the very beginning it is startlingly clear that recuperation and neutralization are a far easier path. Take the industry of “news reporting,” for instance. As the cable channels shift over to 24/7 reporting, it is no longer sufficient to pursue the old spectacular schemata, creating, rather than merely reporting on, the various scandals and sensations. It is not enough to simply position the cameras in a certain spot and observe their effect on the filmed. The news must become co-extensive with the time of life itself. One must, therefore, do more than simply create novelties. In the era of active spectacle, one must create the proper conditions for the novel and newsworthy. But, as we know, the news has been manufactured to produce certain effects since long before the appearance of active spectacle. Reporters rarely pursue their prey, as one is led to believe. Instead, the reported-on must actively solicit coverage, since the various agencies will rarely venture out into the wild of lived experience. Why would they need to, when so much material is already manufactured to their specifications by corporations and governmental entities? Therefore, the periodization described above must be complicated a bit. The transformation that emerges with the video camera and social media is really a generalization of the capacity to produce the true which was, during the classical era of spectacle, limited to certain elites. Active spectacle was, in its way, always nascent within passive spectacle. You just had to pay more for its privileges.

ϕ

Every scandal loves a trial. And this is the age, let’s remember, of the blockbuster trial, the totally televised trial, followed droolingly by the recently developed 24/7 cable news channels still looking for content to fill out the hours. The 1990s: one could tell its story solely through the names King, Simpson, Clinton. And so the trial of the police officers begins, a trial that puts at stake the institution of the police itself, if only because the state must insist, in defending the officers, that their conduct was merely exemplary, that they were simply doing their job. But it is a trial in another sense, an experiment with a new form of publicity and sensationalism that places the courtroom square in the middle of every living room: it is a putting-on-trial of a new kind of reason, a new affect, and the various powers are reckless here in stoking a paranoid desire for apocalyptic violence. (Later, they will understand their own capacities better, and exhibit more circumspection in deploying such powers in unpredictable environments).

No one, therefore, is really all that surprised when – after the police officers who beat Rodney King are pronounced not guilty – thousands upon thousands of the invisible residents of this hypervisible city rise up to smash and burn and loot the very machinery which determines who gets seen and how. In this sense, the Los Angeles riots of 1992 are a rare example of a struggle over the terms of representation which is not a diversion from struggle on the material plane but rather an incitement to it, perhaps because this is not a struggle for representation as much as it is a struggle against representation, one that puts into question the very means of deciding what gets seen or said, rather than the content of such seeing or saying. For a few nights, it promises the self-destruction of all our ways of making things visible or heard, a bonfire of the means of depicting and speaking which the most adventurous avant-garde could only dream about.

As noted, none of this controverts the extent to which these were bread riots, or their late 20th-century equivalent – organized, as is the case with all looting, around a material expropriation of necessaries and luxuries alike. But perhaps, more importantly, crystallized around the hatred of commodities, a hatred whose satisfaction means, in fact, the slaking of a thirst almost as urgent as the need for the use-values themselves. We have to understand this as a period of outright war, when the number of people – black men, in particular – serving prison sentences increased by an order of magnitude, when cops were being trained by Special Forces who brought the “lessons” of the Central American counter-insurgency wars home to South Central Los Angeles. Which is to say that these were matters of life and death as well as recognition – closer to the original Hegelian story of life-and-death struggle for recognition than its pale electoral successors . One must see people stealing the video-cameras and televisions – the big-ticket appliances of which they bad been, for so long, the object – as an attempt to secure their very reality. To become subject, not object. Spectacle, for a brief moment, reveals its own fragility: transmitting, disseminating and relaying antagonism rather than muting and deflecting it. For a moment, self-representation is not the newest face of domination, an internalization of the enemy, but promises the destruction of all mediation, all intermediaries. Bill Cosby goes on TV to urge the rioters to return to their homes and watch the season finale of The Cosby Show.

In a certain manner, this project of expropriating the means of representation and transmission is an eloquent literalization of the music of the riots itself, hip hop, a music based upon the transformation of consumer electronics – the turntable, the home stereo – into instruments of musical production. Technologies which were once means of production – capital goods, in other words – become consumer products. But then, in a final turn, these consumer products become, once again, the means of production for a new generation of untrained musicians whose output is based upon appropriation and sampling, which are a particular kind of consumption-become-production. All the dreams of decentralization and horizontality which we will fondly remember in their suffusion through the 1990s begin here: the politics of the rhizome, the network, the galaxy, the autonomous nuclei. They begin here, with mass-produced consumer electronics whose drive is not only toward cheapening but miniaturization. It’s not just that information wants to be free; it wants to become a kind of gas, an array of volatilized nano-machines, circumambient, hyperlocative. “Copwatch” organizations and other counter-surveillance projects – taking the Rodney King video as their clarion call – spread faster and farther as the price of the camcorder falls, as it becomes smaller, lighter. They spread at the same rate as CCTV spreads, adorning every street corner in cities like Chicago and London. And, of course, tactical representation finds itself eminently suited to the politics of representation that dominates the liberal multiculturalism of the 1990s. An entire ethos is built upon this pedagogical and epistemological basis. Information and its dissemination becomes the means by which everyone can have their voice. The independent media initiatives that emerge at the end of the decade essentially elaborate upon this foundation: the free circulation of information as a placeholder for other freedoms.

In Los Angeles during the 1990s, this made a certain sense. We will render power visible, we thought. We will show everyone that the emperor has no clothes. We will show everyone who they are. Like the sunglasses in John Carpenter’s They Live, capable of revealing the slithering horror beneath the familiar present which our normal (that is, ideological) vision construes – the camcorder would disclose what others couldn’t see. It would be visceral and immediate in a way that language cannot, even if language is capable of making finer distinctions. But it would also make things seem unreal. It would also be an instrument of de-realization, shifting struggle from the ground of praxis toward the ground of epistemology, and from there toward questions of knowledge and ideology which, presumably, only the technicians of politics can solve for us. And so, in the wake of the riots, the recuperation begins. Like all recuperations, it will seem to precede, somehow, the acts of resistance from which it sprang, if only by erasing their real origin.

ϕ

The shift from static, passive spectacle to dynamic, active spectacle is nothing other than this process of recuperation and subsumption. Charged with reproducing the social relations necessary for the continuation of capitalism, spectacle adjusts to its critique, subsumes it, offers up a series of false alternatives decorated in the bracing negativity of the day. Spectacle stages its own negation, the way a hunted criminal might stage her own death by leaving behind someone else’s corpse in place of her own. Spectacle in its classical phase proceeded by replacing all exchanges between persons with dead phrases and images subject to the whims of the commodity, with static and chatter designed to baffle and delay any intelligent action. It thwarted any meaningful activity by all manner of phantasms, false leads, cul-de-sacs and proxies. But its weakness was that it required the constant ministrations of a class of petit-bourgeois intermediaries, clericals, creatives and technicians, themselves the group most deeply colonized by spectacle. Active spectacle, on the other hand, does away with some portion of this class. Active spectacle is, first and foremost, a labor-saving device. It is a way of getting the consumer of spectacle to become the producer of spectacle, all the while pretending that this voluntary labor is, in fact, a form of freedom and greater choice, an escape from the stultifying imposition of this or that taste which the vertical power of the passive spectacle forces on us.

This is an alternate way to talk about the recuperation of negativity which has been ongoing since the 1970s. Everyone is familiar with this – the graffiti kids who add value to a neighborhood by fucking it up, giving it the right degree of color and edginess, and perhaps inspiring, with their visual style, some future generation of designers and advertisers. Eventually, as we all know, the great spread of alternative lifestyles and forms and subcultures that follow in the wake of the aborted liberations of the 1960s and 1970s find their final resting place in the boutique or the museum, and this process – let’s call it the turnover time of recuperation – is constantly accelerating. But the paradigmatic case here, the final profusion, comes in the realm of technology: the merger of home and office, work and leisure, effected by the personal computer means that one finally becomes the consumer of one’s own self-designed fantasias. These are tools for taking the dream of autonomy concealed in the notion of self-management and converting it into an efficient machine for exploitation and control – a way of making the cop and the boss immanent to our every activity. The miniaturization of information technology – which also means the recession and involution of all its working components, so that the surface can be humanized, made aesthetically pleasing – allows for control to be decentralized, networked, built from the ground up in new shapes and flavors. It is a way of spreading the bureaucratic protocols of office technology across the entirety of society.

Once the internet is streamlined, cheapened, and made easy-to-use, an entire political ontology gets attached to “the net”– its origin in military-industrial and bureaucratic protocols hidden beneath warm, “user-friendly” layers which promise the end of a merely unilateral media, promise a new media based upon participation, self-actualization, democracy, promise to free us from reliance upon authoritarian or hierarchical communication. It is a media, as many will claim, which encourages dissent rather than suppresses it, a media no longer dependent upon the massifications and conformities of the broadcast form. No longer the passive receiver of consumable representations, we become the co-creators of the conditions of our own subordination – we don’t merely choose from the 1001 flavors of horror on offer but actively create them, share them, use them as the basic substance of our connections to others, whether friend, enemy, or acquaintance. We are free to make and remake ourselves endlessly in the shape of a thousand avatars and personae. Never mind that these technologies depend, at root, upon standardized lumps of silica and copper and plastic, on the smoothing of electrical switches into reified patterns and routines, on the transformation of matter into algebra. For the various “independent media” initiatives, the internet is as fundamental an apparatus as the video-camera was for the copwatch programs.

The advent of blogging and the various social networking sites – MySpace, then Facebook, and finally (once everyone realized that anything worth saying in such fora could be said in 140 characters or not at all) Twitter – essentially build upon the protocols, models and values established by “independent media.” They represent the depoliticization of these forms, something easy to do since, from the start, “indymedia” as a concept was built around a false formalism. Because the website proved itself such an effective tool for the coordination of thousands of bodies at the counter-summit – distributing information about the location of rioting, tactical weaknesses, arrestees, food and medical services – it was obvious that it could also serve to coordinate thousands of bodies in other kinds of campaigns: advertising campaigns, fundraising drives, mobilizations for this or that political candidate. Social media: the term means that our sociality itself has become what is communicated, has become content, not form. No longer do we merely read the news: now we can write it, now we can make it even more banal and empty than before. Yes, everyone their 15 minutes of celebrity, except now these 15 minutes are broken up into millisecond-sized atoms of time, salted throughout our hours and days, held by invisible readers and contacts and “friends.” Here the voyeur meets the exhibitionist. Here the exhibitionist meets the voyeur. Here the most gregarious sociality and the most contorted narcissism are absolutely identical. Tellingly, new cellular phones now contain two cameras – one facing out into the world, away from the screen, and one reflecting back upon the ego.

But because active spectacle takes hostility toward spectacle as one of its primary fuel sources, because it is always cultivating such antagonism at the same time as it neutralizes it, there is always the possibility of explosive breakdown, the possibility that a violent proletarian content may become contagious. Such was the case when the WikiLeaks affair – initially subsumed almost completely by a libertarian logic of transparency and the free flow of information – transformed into a low-intensity cyberwar with the arrival of Anonymous, LulzSec and others. Although originally entirely devoted to a kind of Assangiste framework that cared only about the free flow of internet information (namely, porn, pirated media and software) – a position that still dominates much of their discourse – these groups eventually became frameworks into which more and more radical content could get injected, and now one routinely hears Anonymous communiqués cite various insurrectionary watchwords, and describe their enemy not as censorship but capitalism and the state as such. Perhaps more significantly, we can note the way in which technologies like Twitter – originally developed so that we could better market commodities to each other – are now used for all-out assaults on the commodity, used to organize proletarian flashmobs and rioting in the suburbs of London, in Baltimore and Kansas City and Milwaukee.

ϕ

10 years later, we all recognize the limits of the anti-globalization movement, limits that still constantly reimpose themselves even if we have moved into a new age of austerity and riot. The antiglobalization movement failed by winning all that it won on the ground of representation alone. Not only were its politics essentially a representational critique of the representational (direct democracy); not only did it fight via representational means (media activism); but more importantly its focus remained limited to the representatives of multi-national capital: the institutions and ambassadors responsible for maintaining the international monetary and trade system. Over and over again, the countersummit conflated the representative institutions for the thing itself – moving back and forth between an attack on a proxy for capital, and capital itself.

It is obvious that this imprisonment within the imaginary is an effect of the very basis – a technopolitical basis – upon which these struggles are conducted, rather than the other way around. Representation is means, content and form: everyone has a camera at the protest and the dangers here are not only that one is unwittingly capturing evidence for the state, but that we are therefore entrapped within the imaginary, our finest moments rendered pornographic – that is, made into a simple conduit for charge or sensation, upon which any idea, no matter how fascist, can be overlaid.

Let’s put it bluntly: with only a few exceptions, the journalists whose presence at the demonstration or riot is vouchsafed by the camera are nothing other than the agents of the state, little different than informants in their attitude toward what transpires. Their feigned neutrality is the neutrality of “the citizen,” of public opinion, an enemy position. Except when used with incredible care and sensitivity and artfulness, the camera is basically an instrument of neutralization. We can have no tolerance for those who attempt to use our antagonism as stepping-stones in their career; nor can we tolerate the special rights and privileges which journalists want to claim, as if holding a camera or press-badge entitled them to exceptional status. This is liberalism’s phantasm – the materialization of the abstract personhood which has mangled our lives for centuries. In any case, the police no longer give a fuck. Everywhere there are new laws prohibiting the filming of police and they now routinely arrest people because they have a camera, not only to protect themselves from scandal but to collect evidence.

ϕ

Surveillance and countersurveillance, spectacle and counterspectacle, then, merge together into one representational surround. Riot footage becomes an advertisement for jeans, as if shopping and destroying a shop were equivalent activities. If counter-surveillance aims to light up the unevenesses, the blotches and stains that the picture of the world hides, it also runs the risk, as all struggles do, of fighting on the ground of representation alone, and of winning thusly the mere representation of winning. Though we do not use the term in this sense exclusively, this is what it means to speak of “politics” in the pejorative sense – the translation of struggle to the realm of representation, either through the substitutionism of the assembly, the party, or the image-world. It means to fight representatives and proxies endlessly and pyrrhically, because capital is nothing more than this process of creating proxies. The catch is that, because they still believe that the question of representation is the question that must be answered, many anti-representational strategies – the participatory democracy of the general assembly, for instance – remain trapped within politics in the same way that the atheist remains trapped within religion because he or she takes seriously the question of god’s existence.

ϕ

The one exception to this story of diversion to the ground of representation is the black bloc, which by its very nature refuses visibility. The black bloc emerges as a counterweight to the regime of hypervisibilty, emerges as the avenging angel of all that has been cast into the burning hell of the overlit world. It conjures a black spot which makes the illumination of the world all the more severe; it is a kind of “darkness visible,” as Milton says of Lucifer’s resting place. But at what point does this darkness become only its own visibility, a set of predictable movements and moments, easily recognized simply because it is the thing which refuses recognition? How often is it the case that the plate glass of the bank is shattered but the camera lens, with all of its frightening transparency, remains? One of the problems, here, as others have noted, is that the black bloc often distinguishes itself from the larger mass of people in the streets. Even if all identity inside the group is quickly liquidated by masks and black clothing, the bloc still affirms an identity – albeit a negative one – with regard to its environment. Rather than attempting an absolute negation of visibility, we might instead cultivate a kind of chiaroscuro effect, attending to the ebb and flow of light and shadow naturally at play in such situations. True anonymity is the anonymity of the crowd, the anonymity of people in regular dress who begin to throw rocks at cops, loot stores, and burn cars, and whose anonymity comes from their subtle commonalities with thousands upon thousands of other figures. (Though, of course, concealing one’s face is a precaution that can never be dispensed with, and should be actively encouraged on all occasions). The more it becomes possible for the active minority to merge with the anonymous crowd, to dissolve and abolish its own specificity at the height of the attack, the closer we come to the kind of riot which continues past the first night. Whether people continue to use black blocs is a practical matter, of course, and has to do with local conditions which cannot be evaluated in the abstract. But we must be honest about the limitations of the form, and note that there are anonymities superior to the black bloc, forms of self-abolition that do not establish a radical identity apart from the larger mass of people in the streets.

It is not, therefore, merely a question of creating “zones of offensive opacity.” Every opacity has its complementary transparency, and we must attend to both. We must be willing to make ourselves visible here, invisible there, and neither everywhere. Language, in this sense, is often superior to the photograph’s ontological trickery. We all recognize the power of the well-written communiqué or manifesto, the well-designed poster with the explosive phrase. This power is art, poetry, art that lives on, nevertheless, after the death of art. Taken up on the field of battle, conjoined with real practices of negation, this poetry – the beautiful language of our century, as it was once called – has a real explosive force, one that does not pass through reason and understanding alone, but which trades on affect, perception, sensation. The technical means we have at present for conveying such affects and perceptions are, let’s admit it, very weak – a series of pre-given filters and plug-ins which we can apply to this or that image or idea. Why is it, then, that the various radical milieus do not at present produce more films, more poetry and novels, communicate through drawings and illustrated stories as well as photographs? Why must we subordinate ourselves to a barren plain-style, on the one hand, and a mawkish sentimentalism on the other? Why do we accept the self-evidence of the very images which the state uses to speak about us? In expanding our capacities for thought and communication, in expanding the formal and technical means for such, we must learn to speak of and to each other in a way that takes exception with the way we are spoken about, which takes exception with the language of the status quo, the state. This is a matter of how we say such things as much as what we say. Active spectacle, let’s remember, hides the issue of content by allowing for modest transformations of the form of communication. This is why the transposition of the locus of questioning from what to how relies on a weak understanding of recent history. Asking how has, for a long time now, been a counter-revolutionary question.

ϕ

Late in life, in the midst of his drunken melancholia and paranoid rumination, Guy Debord entertained himself by inventing a chess-like game of war in which the chief innovation was the establishment of lines of communication between pieces. Pieces that were unconnected via intermediating, communicating pieces could not move at all. Debord understood, in this game as well as in his writing, that all struggles have a communicative dimension. The difference, however, between the situation we confront and the situation in Debord’s game is that we are forced to use the very same lines of communication as our enemy. Every one of our communications is at one and the same time an enemy transmission, part of the enemy system, part of spectacle. To operate effectively, to turn spectacle in its active form against itself, we have to examine our communications both from our own standpoint and the enemy’s, developing forms of communication which are transparent for us but opaque for them, which allow us to communicate and expand our ability to think and perceive collectively without assisting the state in its attempts to monitor and obstruct us, and which reach out to sympathizers, fellow-travelers, and comrades without giving away vital information to the enemy.

In this regard, matters of style are at one and the same time matters of survival.

ϕ

Research & Destroy

Oakland, CA

April, 2012

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anti-capitalism, death, decomposition, may day, oakland, oakland commune, Occupy oakland, occupy wall street

From Bayofrage:

May 1, decomposition and the coming antagonisms

THE COMMUNE

For those of us in Oakland, “Occupy Wall Street” was always a strange fit. While much of the country sat eerily quiet in the years before the Hot Fall of 2011, a unique rebelliousness that regularly erupted in militant antagonisms with the police was already taking root in the streets of the Bay. From numerous anti-police riots triggered by the execution of Oscar Grant on New Year’s Day 2009, to the wave of anti-austerity student occupations in late 2009 and early 2010, to the native protest encampment at Glen Cove in 2011, to the the sequence of Anonymous BART disruptions in the month before Occupy Wall Street kicked off, our greater metropolitan area re-emerged in recent years as a primary hub of struggle in this country. The intersection at 14th and Broadway in downtown Oakland was, more often than not, “ground zero” for these conflicts.

If we had chosen to follow the specific trajectory prescribed by Adbusters and the Zucotti-based organizers of Occupy Wall Street, we would have staked out our local Occupy camp somewhere in the heart of the capitol of West Coast capital, as a beachhead in the enemy territory of San Francisco’s financial district. Some did this early on, following in the footsteps of the growing list of other encampments scattered across the country like a colorful but confused archipelago of anti-financial indignation. According to this logic, it would make no sense for the epicenter of the movement to emerge in a medium sized, proletarian city on the other side of the bay.

We intentionally chose a different path based on a longer trajectory and rooted in a set of shared experiences that emerged directly from recent struggles. Vague populist slogans about the 99%, savvy use of social networking, shady figures running around in Guy Fawkes masks, none of this played any kind of significant role in bringing us to the forefront of the Occupy movement. In the rebel town of Oakland, we built a camp that was not so much the emergence of a new social movement, but the unprecedented convergence of preexisting local movements and antagonistic tendencies all looking for a fight with capital and the state while learning to take care of each other and our city in the most radical ways possible.

This is what we began to call The Oakland Commune; that dense network of new found affinity and rebelliousness that sliced through seemingly impenetrable social barriers like never before. Our “war machine and our care machine” as one comrade put it. No cops, no politicians, plenty of “autonomous actions”; the Commune materialized for one month in liberated Oscar Grant Plaza at the corner of 14th & Broadway. Here we fed each other, lived together and began to learn how to actually care for one another while launching unmediated assaults on our enemies: local government, the downtown business elite and transnational capital. These attacks culminated with the General Strike of November 2 and subsequent West Coast Port Blockade.

In their repeated attacks on Occupy Oakland, the local decolonize tendency is in some ways correct.[1] Occupy Wall Street and the movement of the 99% become very problematic when applied to a city such as Oakland and reek of white liberal politics imposed from afar on a diverse population already living under brutal police occupation. What our decolonizing comrades fail to grasp (intentionally or not) is that the rebellion which unfolded in front of City Hall in Oscar Grant Plaza does not trace its roots back to September 17, 2011 when thousands of 99%ers marched through Wall Street and set up camp in Lower Manhattan. The Oakland Commune was born much earlier on January 7, 2009 when those youngsters climbed on top of an OPD cruiser and started kicking in the windshield to the cheers of the crowd. Thus the name of the Commune’s temporarily reclaimed space where anti-capitalist processes of decolonization were unleashed: Oscar Grant Plaza.

Why then did it take nearly three years for the Commune to finally come out into the open and begin to unveil its true potential? Maybe it needed time to grow quietly, celebrating the small victories and nursing itself back to health after bitter defeats such as the depressing end of the student movement on March 4, 2010. Or maybe it needed to see its own reflection in Tahrir, Plaza del Sol and Syntagma before having the confidence to brazenly declare war on the entire capitalist order. One thing is for sure. Regardless of Occupy Wall Street’s shortcomings and the reformist tendencies that latched on to the movement of the 99%, the fact that some kind of open revolt was rapidly spreading like a virus across the rest of the country is what gave us the political space in Oakland to realize our rebel dreams. This point cannot be overemphasized. We are strongest when we are not alone. We will be isolated and crushed if Oakland is contained as some militant outlier while the rest of the country sits quiet and our comrades in other cities are content consuming riot porn emerging from our streets while cheering us on and occasionally coming to visit, hoping to get their small piece of the action.

THE MOVEMENT

For a whole generation of young people in this country, these past six months have been the first taste of what it means to struggle as part of a multiplying and complex social movement that continually expands the realm of possibilities and pushes participants through radicalization processes that normally take years. The closest recent equivalent is probably the first (and most vibrant) wave of North American anti-globalization mobilizations from late 1999 through the first half of 2001. This movement also brought a wide range of tendencies together under a reformist banner of “Fair Trade” & “Global Justice” while simultaneously pointing towards a systemic critique of global capitalism and a militant street politics of disruption.

The similarities end there and this break with the past is what Occupy got right. Looking back over those heady days at the turn of the millennia (or the waves of summit hopping that followed), the moments of actually living in struggle and experiencing rupture in front of one’s eyes were few and far between. They usually unfolded during a mass mobilization in the middle of one “National Security Event” or another in some city on the other side of the country (or world!). The affinities developed during that time were invaluable, but cannot compare to the seeds of resistance that were sown simultaneously in hundreds of urban areas this past Fall.

It makes no sense to overly fetishize the tactic of occupations, no more than it does to limiting resistance exclusively to blockades or clandestine attacks. Yet the widespread emergence of public occupations qualitatively changed what it means to resist. For contemporary American social movements, it is something new to liberate space that is normally policed to keep the city functioning smoothly as a wealth generating machine and transform it into a node of struggle and rebellion. To do this day after day, rooted in the the city where you live and strengthening connections with neighbors and comrades, is a first taste of what it truly means to have a life worth living. For those few months in the fall, American cities took on new geographies of the movement’s making and rebels began to sketch out maps of coming insurrections and revolts.

This was the climate that the Oakland Commune blossomed within. In those places and moments where Occupy Wall Street embodied these characteristics as opposed to the reformist tendencies of the 99%’s nonviolent campaign to fix capitalism, the movement itself was a beautiful thing. Little communes came to life in cities and towns near and far. Those days have now passed but the consequences of millions having felt that solidarity, power and freedom will have long lasting and extreme consequences.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the movement is now decomposing and that we are now, more or less, alone, passing that empty park or plaza on the way to work (or looking for work) which seemed only yesterday so loud and colorful and full of possibilities.

All of the large social movements in this country following the anti-globalization period have heated up quickly, bringing in millions before being crushed or co-opted equally as quickly. The anti-war movement brought millions out in mass marches in the months before bombs began falling over Baghdad but was quickly co-opted into an “Anybody but Bush” campaign just in time for the 2004 election cycle. The immigrant rights movement exploded during the spring of 2006, successfully stopping the repressive and racist HR4437 legislation by organizing the largest protest in US history (and arguably the closest thing we have ever seen to a nation-wide general strike) on May 1 of that year [2]. The movement was quickly scared off the streets by a brutal wave of ICE raids and deportations that continue to this day. Closer to home, the anti-austerity movement that swept through California campuses in late 2009 escalated rapidly during the fall through combative building occupations across the state. But by March 4, 2010, the movement had been successfully split apart by repressing the militant tendencies and trapping the more moderate ones in an impotent campaign to lobby elected officials in Sacramento. Such is the rapid cycle of mobilization and decomposition for social movements in late capitalist America.

THE DECOMPOSITION

So what then killed Occupy? The 99%ers and reactionary liberals will quickly point to those of us in Oakland and our counterparts in other cites who wave the black flag as having alienated the masses with our “Black Bloc Tactics” and extremist views on the police and the economy. Many militants will just as quickly blame the sinister forces of co-optation, whether they be the trade union bureaucrats, the 99% Spring nonviolence training seminars or the array of pacifying social justice non-profits. Both of these positions fundamentally miss the underlying dynamic that has been the determining factor in the outcome thus far: all of the camps were evicted by the cops. Every single one.

All of those liberated spaces where rebellious relationships, ideas and actions could proliferate were bulldozed like so many shanty towns across the world that stand in the way of airports, highways and Olympic arenas. The sad reality is that we are not getting those camps back. Not after power saw the contagious militancy spreading from Oakland and other points of conflict on the Occupy map and realized what a threat all those tents and card board signs and discussions late into the night could potentially become.

No matter how different Occupy Oakland was from the rest of Occupy Wall Street, its life and death were intimately connected with the health of the broader movement. Once the camps were evicted, the other major defining feature of Occupy, the general assemblies, were left without an anchor and have since floated into irrelevance as hollow decision making bodies that represent no one and are more concerned with their own reproduction than anything else. There have been a wide range of attempts here in Oakland at illuminating a path forward into the next phase of the movement. These include foreclosure defense, the port blockades, linking up with rank and file labor to fight bosses in a variety of sectors, clandestine squatting and even neighborhood BBQs. All of these are interesting directions and have potential. Yet without being connected to the vortex of a communal occupation, they become isolated activist campaigns. None of them can replace the essential role of weaving together a rebel social fabric of affinity and camaraderie that only the camps have been able to play thus far.

May 1 confirmed the end of the national Occupy Wall Street movement because it was the best opportunity the movement had to reestablish the occupations, and yet it couldn’t. Nowhere was this more clear than in Oakland as the sun set after a day of marches, pickets and clashes. Rumors had been circulating for weeks that tents would start going up and the camp would reemerge in the evening of that long day. The hundreds of riot police backed by armored personnel carriers and SWAT teams carrying assault rifles made no secret of their intention to sweep the plaza clear after all the “good protesters” scurried home, making any reoccupation physically impossible. It was the same on January 28 when plans for a large public building occupation were shattered in a shower of flash bang grenades and 400 arrests, just as it was on March 17 in Zucotti Park when dreams of a new Wall Street camp were clubbed and pepper sprayed to death by the NYPD. Any hopes of a spring offensive leading to a new round of space reclamations and liberated zones has come and gone. And with that, Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Oakland are now dead.

THE FUTURE

If one had already come to terms with Occupy’s passing, May 1 could actually be viewed as an impressive success. No other 24 hour period in recent memory has unleashed such a diverse array of militancy in cities across the country. From the all day street fighting in Oakland, to the shield bloc in LA, to the courageous attempt at a Wildcat March in New York, to the surprise attack on the Mission police station in San Francisco, to the anti-capitalist march in New Orleans, to the spectacular trashing of Seattle banks and corporate chains by black flag wielding comrades, the large crowds which took to the streets on May 1 were no longer afraid of militant confrontations with police and seemed relatively comfortable with property destruction. This is an important turning point which suggests that the tone and tactics of the next sequence will be quite different from those of last fall.

Yet the consistent rhythm and resonance of resistance that the camps made possible has not returned. We are once again wading through a depressing sea of everyday normality waiting for the next spectacular day of action to come and go in much the same way as comrades did a decade ago in the anti-globalization movement or the anti-war movement. In the Bay Area, the call to strike was picked up by nurses and ferry workers who picketed their respective workplaces on May 1 along with the longshoremen who walked off the job for the day. This display of solidarity is impressive considering the overall lack of momentum in the movement right now. Still, it was not enough of an interruption in capital’s daily flows to escalate out of a day of action and into a general strike like we saw on November 2.

And thus we continue on through this quieter period of uncertainty. We still occasionally catch glimpses of the Commune in those special moments when friends and comrades successfully break the rules and start self organizing to take care of one another while simultaneously launching attacks against those who profit from mass immiseration. We saw this off and on during the actions of May 1, or in the two occupations of the building at 888 Turk Street in San Francisco or most recently on the occupied farmland that was temporarily liberated from the University of California before being evicted by UCPD riot police a few days ago. But with the inertia of the Fall camps nearly depleted, the fierce but delicate life of our Commune relies more and more on the vibrancy of the rebel social relationships which have always been its foundation.

The task ahead of us in Oakland and beyond is to search out and nurture new means of finding each other. We are quickly reaching the point where the dead weight of Occupy threatens to drag down the Commune into the dust bin of history. We need to breathe new life into our network of rebellious relationships that does not rely on the Occupy Oakland general assembly or the array of movement protagonists who have emerged to represent the struggle. This is by no means an argument against assemblies or for a retreat back into the small countercultural ghettos that keep us isolated and irrelevant. On the contrary, we need more public assemblies that take different forms and experiment with themes, styles of decision making (or lack there of) and levels of affinity. We need new ways to reclaim space and regularize a contagious rebel spirit rooted in our specific urban contexts while breaking a losing cycle of attempted occupations followed by state repression that the movement has now fallen into. Most of all, we need desperately to stay connected with comrades old and new and not let these relationships completely decompose. This will determine the health of the Commune and ultimately its ability to effectively wage war on our enemies in the struggles to come.

Some Oakland Antagonists

May 2012

NOTES:

[1] The decolonize tendency emerged in Oakland and elsewhere as a people of color and indigenous led initiative within the Occupy movement to confront the deep colonialist roots of contemporary oppression and exploitation. Decolonize Oakland publicly split with Occupy on December 5, 2011 after failing to pass a proposal in the Occupy Oakland general assembly to change the name of the local movement to Decolonize Oakland. For more information on this split see the ‘Escalating Identity’ pamphlet: http://escalatingidentity.wordpress.com/

[2] The demonstrations on May 1, 2006, called El Gran Paro Estadounidense or The Great American Boycott, were the climax of a nationwide series of mobilizations that had begun two months earlier with large marches in Chicago and Los Angeles as well as spontaneous high school walkouts in California and beyond. Millions took to the streets across the country that May 1, with an estimated two million marching in Los Angeles alone. Entire business districts in immigrant neighborhoods or where immigrants made up the majority of workers shut down for the day in what some called “A Day Without an Immigrant”.

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anarchy, anti-capitalism, anti-police, bay area, chaos, fuck the police, may day, oakland, Occupy oakland, occupy wall street, riot, vandalism, violence

From Anarchist News:

Based on media coverage of the past week, here are some highlights:

—Monday April 30th, San Francisco, nighttime—

-Several hundred people march from Dolores Park behind a banner reading ‘Strike Early; Strike Often.

-First police cruiser to respond is covered with paint bombs and has its windows smashed by a garbage can, forcing it to retreat.

-Police who attempt to respond are forced back inside the Mission Police station when the crowd arrives and begins attacking. Windows are broken. the building, several vehicles, and a few cops are rained upon by paint bombs.

-Roughly a dozen yuppie business on 18th street and on Valencia have their windows broke and/or are hit with paint bombs.

-The fence is torn down from around a multi-million dollar condo construction site, which then loses its brand new windows.

-Several cars are have their windows broken and tires slashed. The vast majority of which were luxury cars. One luxury SUV is set on fire.

—Tuesday May 1st, Oakland, daytime—

-Snake marches leave strike stations and attempt to force the closure of several banks, businesses and government agencies (including CPS). Several scuffles break out with police and do-gooders. One such bank is entered and trashed from within.

-Police attack, fire crowd control weaponry, arrests, de-arrests, all out brawling.

-Several banks and ATMs suffer vandalism. As do a handful of businesses, including Mcdonalds.

-Windows smashed out of Police van which is trying to make arrests.

-Windows smashed on one news media van parked at Oscar Grant Plaza, tires slashed on another.

-Plaza is temporarily re-occupied and the surrounding area covered in graffiti.

—Tuesday May 1st, San Francisco, daytime—

-Building at 888 Turk is re-occupied and declared to be the SF Commune once again. Banner dropped from the facade reading ‘ACAB’.

-Individuals on the roof of the SF Commune fight the police who are attempting to evict it. One throws several pipes at SFPD vehicles, breaking their windows and otherwise damaging them. Another masked individual throws bricks at the police, knocking down officers and those standing too near to them.

—Tuesday May 1st, Oakland, nighttime—

-Police attack demonstrators at Oscar Grant Plaza, all hell breaks lose. Running battles between police and demonstrators all throughout downtown. Police use snatch squads and brute force.

-Many dumpsters and trash cans are set on fire along Broadway.

-Banks are attacked by demonstrators evading the swarming riot police.

-Two OPD cruisers are set on fire.

-CalTrain building is attacked

-Four Fremont Police vehicles have their windows and/or tires taken out.

Strength to those arrested in relation to the May Day events in the Bay, and elsewhere.

Freedom for Pax, and all other comrades imprisoned and awaiting trial.

Love to all the rebels who demonstrated their ferocity this week, including those who carried out targeted attacks in Bloomington, Portland, Memphis, Denver and NOLA.

Particular affection for the comrades in Seattle and New York: Seattle which made us cry in the face of pure beauty; and NYC which tried its hardest to do the damn thing, in spite of having to confront the world’s seventh largest standing army in order to do so.

Everything for Everyone! Let’s abolish this absence!

Death to the existent!

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: brawls, cops, fighting, may day, oakland, Occupy oakland, opd, police, the oakland commune, violence

According to the OPD:

Today the City of Oakland facilitated marches, demonstrations and protests of various kinds at locations throughout the City. The City of Oakland is committed to facilitating peaceful expressions of free speech rights, and protecting personal safety and property; however we have continuously stated that we will not tolerate destruction or violence.

Today’s strategy focused on swiftly addressing any criminal behavior that would

damage property or jeopardize public or officer safety. Officers were able to

identify specific individuals in the crowd committing unlawful acts and quickly

arrest them so the demonstration could continue peacefully.

Given the anticipated size of the crowd, mutual aid was called early in the day to

enhance OPD staffing.

Protests started at 7 am with about 45 people boarding buses heading to ferry

stations throughout the Bay Area. Meanwhile, protesters set up a series of marches, pickets and blockades at locations throughout the downtown area.

Around 11 am, groups converged in Frank H. Ogawa Plaza before splintering into two groups that headed northbound on Broadway, where some isolated incidents of vandalism occurred.

At about 12:30 this afternoon, a large crowd assembled at 14th and Broadway and

some protesters began throwing objects at officers who were attempting to make

an arrest. The crowd surrounded the officers and small amounts of gas were

deployed on three occasions in limited areas to disperse the specific small groups

of people who were committing the violent acts.

As of 2 pm, a crowd of about 400 had assembled at 14th and Broadway and in

Frank H. Ogawa Plaza, then headed to Fruitvale to join a permitted march. That

march began at 3 pm and grew to about 3,500 people who eventually converged at

Frank H. Ogawa Plaza in the early evening. By about 8 pm, most of the crowd had

peacefully dispersed; about 300 – 500 people remained.

Starting at about 8:30 pm, OPD issued two dispersal orders to clear the area at 14th and Broadway, 15th and Broadway/Telegraph, and Frank H. Ogawa Plaza. The

orders came shortly after OPD had attempted to arrest an individual. A crowd of

about 300 people surged forward and began throwing bottles and other objects.

Although most of the demonstrators heeded the dispersal order, a group of about

60 people splintered off in about a dozen groups, running through the Plaza and

northbound on Telegraph Avenue and Broadway.

OPD’s focus tonight is to keep the groups from reorganizing, and to minimize

vandalism and damage to public and private property.

Arrests

· 25 arrests confirmed (1 felony arrest for an assault on an officer; 2 felony

arson arrests, including an arsonist who burned a police vehicle)

Preliminary Vandalism/Damage Assessment

Earlier today:

· Minor vandalism/graffiti at Bank of America at Kaiser Center

· Vandalism at Bank of the West (2127 Broadway)

· OPD van had windows broken

· News media vehicle had tires punctured

Following 8:30 pm dispersal orders:

· Fire reported at 19th and Broadway

· Windows broken at Wells Fargo Bank (20th and Franklin)

· OPD car on fire in 1300 block of Franklin

· Car on fire near Internal Affairs Division at Frank Ogawa Plaza

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: flashbang, fuck the police, insurrection, juggalos, news van, oakland, oakland commune, oscar grant, police, street battles

From Anarchist News:

Let us start by apologizing; that our words may be incoherent, our thoughts scattered and our tone overly emotional. Forgive us, because the ringing in our ear continues to interrupt our thinking, because our eyes are bleary and we’re weighed upon by the anxiety and trauma of our injuries and the imprisonment of the ones we love. As most of you are well-aware: after a full day and night of street battles in Oakland, we were defeated in our efforts to occupy a large building for the purposes of establishing an social center. We’re writing, in part, to correct the inaccuracies and mystifications spewed by the scum Media. But more so as to convey the intensity and the urgency of the situation in Oakland to comrades abroad. To an extent, this is an impossible task. Video footage and mere words must inevitably fail at conveying the ineffable collective experiences of the past twenty-four hours. But as always, here goes.

Yesterday was one of the most intense days of our lives. We say this without hyperbole or bravado. The terror in the streets of Miami or St. Paul, the power in the streets of Pittsburgh or Oakland’s autumn; yesterday’s affect met or superseded each of these. The events of yesterday confronted us as a series of intensely beautiful and yet terrible moments.

—

An abbreviated sequence:

Beautiful words are delivered at Oscar Grant Plaza, urging us to cultivate our hatred for capitalism. Hundreds leave the plaza and quickly become thousands. The police attempt to seize the sound truck, but it is rescued by the swarming crowd. We turn towards our destination and are blocked. We turn another way and are blocked once more. We flood through the Laney campus and emerge to find that we’ve been headed off again. We make the next logical move and somehow the police don’t anticipate it. We’re closer to the building, now surrounded by fences and armed swine. We tear at the fences, downing them in some spots. The police begin their first barrage of gas and smoke. The initial fright passes. Calmly, we approach from another angle.

The pigs set their line on Oak. To our left, the museum; to our right, an apartment complex. Shields and reinforced barricades to the front; we push forwards. They launch flash bangs and bean bags and gas. We respond with rocks and flares and bottles. The shields move forward. Another volley from the swine. The shields deflect most of the projectiles. We crouch, wait, then push forward all together. They come at us again and again. We hurl their shit, our shit, and whatever we can find back at them. Some of us are hit by rubber bullets, others are burned by flashbang grenades. We see cops fall under the weight of perfectly-arced stones For what feels like an eternity, we exchange throws and shield one another. Nothing has felt like this before. Lovely souls in the apartment building hand pitchers of waters from their windows to cleanse our eyes. We’ll take a moment here to express our gratitude for the unprecedented bravery and finesse with which the shield-carrying strangers carried out their task. We retreat to the plaza, carrying and being carried by one another.

We re-group, scheme, and a thousand deep, set out an hour later. Failing to get into our second option, we march onwards towards a third. The police spring their trap: attempting to kettle us in the park alongside the 19th and Broadway lot that we’d previously occupied. Terror sets in; the’ve reinforced each of their lines. They start gassing again. More projectiles, our push is repelled. The intelligence of the crowd advances quickly. Tendrils of the crowd go after the fences. In an inversion of the moment where we first occupied this lot, the fences are downed to provide an escape route. We won’t try to explain the joy of a thousand wild-ones running full speed across the lot, downing the second line of fencing and spilling out into the freedom of the street. More of the cat and mouse. In front of the YMCA, they spring another kettle. This time they’re deeper and we have no flimsy fencing to push through. Their lines are deep. A few dozen act quickly to climb a nearby gate, jumping dangerously to the hard pavement below. Past the gate, the cluster of escapees find a row of several unguarded OPD vans: you can imagine what happened next. A complicit YMCA employee throws opens the door. Countless escape into the building and out the exits. The police become aware of both escape routes and begin attacking and trampling those who try but fail to get out. Those remaining in the kettle are further brutalized and resign to their arrest.

A few hundred keep going. Vengeance time. People break into city hall. Everything that can be trashed is trashed. Files thrown everywhere, computers get it too, windows smashed out. The american flags are brought outside and ceremoniously set to fire. A march to the jail, lots of graffiti, a news van gets wrecked, jail gates damaged. The pigs respond with fury. Wantonly beating, pushing, shooting whomever crosses their path. Many who escaped earlier kettles are had by snatch squads. Downtown reveals itself to be a fucking warzone. Those who are still flee to empty houses and loving arms.

—

A war-machine must intrinsically be also a machine of care. As we write, hundreds of our comrades remain behind bars. Countless others are wounded and traumatized. We’ve spent the last night literally stitching one another together and assuring each other that things will be okay. We still can’t find a lot of people in the system, rumors abound, some have been released, others held on serious charges and have bail set. This care-machine is as much of what we name the Oakland Commune as the encampment or the street fighting. We still can’t count the comrades we can’t find on all our hands combined.

We move through the sunny morning and the illusion of social peace has descended back upon Oakland. And yet everywhere is the evidence of what transpired. City workers struggle to fix their pathetic fences. Boards are affixed to the windows of city hall and to nearby banks (some to hide damage, others simply to hide behind). Power washer try to clear away the charred remains of the stupid flag. One literally cannot look anywhere along broadway without seeing graffiti defaming the police or hyping our teams (anarchy, nortes, the commune, even juggalos). A discerning eye can still find the remnants of teargas canisters and flashbang residue. At the coffeeshops and delis, friends and acquaintances find one another and share updates about who has been hurt and who has been had. Our wounds already begin to heal into what will eventually be scars or ridiculous disfigurements. We hope our lovers will forgive such ugliness, or can come to look at them as little instances of unique beauty. As our adrenaline fades and we each find moments of solitude, we are each hit by the gravity of the situation.

Having failed to take a building, our search continues. We continue to find the perfect combination of trust, planning, intensity and action that can make our struggle into a permanent presence. The commune has and will continue to slip out of time, interrupting the deadliness and horror of the day to day function of society. Threads of the commune continue uninterrupted as the relationships and affinity build over the past months. An insurrectionary process is the one that emboldens these relationships and multiplies the frequency with which the commune emerges to interrupt the empty forward-thrust of capitalist history. To push this process forward, our task is to continue the ceaseless experimentation and imagination which could illuminate different strategies and pathways beyond the current limits of the struggle. Sometimes to forget, sometimes to remember.

—

We’ll conclude with a plea to our friends throughout the country and across borders. You must absolutely not view the events here as a sequence that is separate from your own life. Between the beautiful and spectacular moments in the Bay, you’ll discover the same alienation and exploitation that characterizes your own situation. Please do not consume the images from the Bay as you would the images of overseas rioting or as a netflix subscription. Our hell is yours, and so too is our struggle.

And so please… if you love us as we believe you do, prove it. We wish so desperately that you were with us in body, but we know most of you cannot be. Spread the commune to your own locales. Ten cities have already announced their intentions to hold solidarity demonstrations tonight. Join them, call for your own. If you aren’t plugged into enough of a social force to do so, then find your own ways of demonstrating. With your friends or even alone: smash, attack, expropriate, blockade occupy. Do anything in your power to spread the prevalence and the perversity of our interruption.

for a prolonged conflict; for a permanent presence; for the commune;

some friends in Oakland

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anti-capitalism, blockade, capitalism, economy, general strike, oakland, oakland commune, the bay area, value circulation

From Bay of Rage:

By any reasonable measure, the November 2 general strike was a grand success. The day was certainly the most significant moment of the season of Occupy, and signaled the possibility of a new direction for the occupations, away from vague, self-reflexive democratism and toward open confrontation with the state and capital. At a local level, as a response to the first raid on the encampment, the strike showed Occupy Oakland capable of expanding while defending itself, organizing its own maintenance while at the same time directly attacking its enemy. This is what it means to refer to the encampment and its participants as the Oakland Commune, even if a true commune is only possible on the other side of insurrection.

Looking over the day’s events it is clear that without the shutdown of the port this would not have been a general strike at all but rather a particularly powerful day of action. The tens of thousands of people who marched into the port surpassed all estimates. Neighbors, co-workers, relatives – one saw all kinds of people there who had never expressed any interest in such events, whose political activity had been limited to some angry mumbling at the television set and a yearly or biyearly trip to the voting booth. It was as if the entire population of the Bay Area had been transferred to some weird industrial purgatory, there to wander and wonder and encounter itself and its powers.

Now we have the chance to blockade the ports once again, on December 12, in conjunction with occupiers up and down the west coast. Already Los Angeles, San Diego, Portland, Tacoma, Seattle, Vancouver and even Anchorage have agreed to blockade their respective ports. These are exciting events, for sure. Now that many of the major encampments in the US have been cleared, we need an event like this to keep the sequence going through the winter months and provide a reference point for future manifestations. For reasons that will be explained shortly, we believe that actions like this – direct actions that focus on the circulation of capital, rather than its production – will play a major role in the inevitable uprisings and insurrections of the coming years, at least in the postindustrial countries. The confluence of this tactic with the ongoing attempts to directly expropriate abandoned buildings could transform the Occupy movement into something truly threatening to the present order. But in our view, many comrades continue thinking about these actions as essentially continuous with the class struggle of the twentieth century and the industrial age, never adequately remarking on how little the postindustrial Oakland General Strike of 2011 resembles the Oakland General Strike of 1946.

The placeless place of circulation

The shipping industry (and shipping in general) has long been one of the most important sectors for capital, and one of the privileged sites of class struggle. Capitalism essentially develops and spreads within the matrix of the great mercantile, colonialist and imperial experiments of post-medieval Europe, all of which are predicated upon sailors, ships and trade routes. But by the time that capitalism comes into view as a new social system in the 19th century the most important engine of accumulation is no longer trade itself, but the introduction of labor-saving technology into the production process. Superprofits achieved through mechanized production are funneled back into the development and purchase of new production machinery, not to mention the vast, infernal infrastructural projects this industrial system requires: mines and railways, highways and electricity plants, vast urban pours of wood, stone, concrete and metal as the metropolitan centers spread and absorb people expelled from the countryside. But by the 1970s, just as various futurologists and social forecasters were predicting a completely automated society of superabundance, the technologically-driven accumulation cycle was coming to an end. Labor-saving technology is double-edged for capital. Even though it temporarily allows for the extraction of enormous profits, the fact that capital treats laboring bodies as the foundation of its own wealth means that over the long term the expulsion of more and more people from the workplace eventually comes to undermine capital’s own conditions of survival. Of course, one of the starkest horrors of capitalism is that capital’s conditions of survival are also our own, no matter our hatred. Directly or indirectly, each of us is dependent on the wage and the market for our survival.

From the 1970s on, one of capital’s responses to the reproduction crisis has been to shift its focus from the sites of production to the (non)sites of circulation. Once the introduction of labor-saving technology into the production of goods no longer generated substantial profits, firms focused on speeding up and more cheaply circulating both commodity capital (in the case of the shipping, wholesaling and retailing industries) and money capital (in the case of banking). Such restructuring is a big part of what is often termed “neoliberalism” or “globalization,” modes of accumulation in which the shipping industry and globally-distributed supply chains assume a new primacy. The invention of the shipping container and container ship is analogous, in this way, to the reinvention of derivatives trading in the 1970s – a technical intervention which multiplies the volume of capital in circulation several times over.

This is why the general strike on Nov. 2 appeared as it did, not as the voluntary withdrawal of labor from large factories and the like (where so few of us work), but rather as masses of people who work in unorganized workplaces, who are unemployed or underemployed or precarious in one way or another, converging on the chokepoints of capital flow. Where workers in large workplaces –the ports, for instance– did withdraw their labor, this occurred after the fact of an intervention by an extrinsic proletariat. In such a situation, the flying picket, originally developed as a secondary instrument of solidarity, becomes the primary mechanism of the strike. If postindustrial capital focuses on the seaways and highways, the streets and the mall, focuses on accelerating and volatilizing its networked flows, then its antagonists will also need to be mobile and multiple. In November 2010, during the French general strike, we saw how a couple dozen flying pickets could effectively bring a city of millions to a halt. Such mobile blockades are the technique for an age and place in which production has been offshored, an age in which most of us work, if we work at all, in small and unorganized workplaces devoted to the transport, distribution, administration and sale of goods produced elsewhere.

Like the financial system which is its warped mirror, the present system for circulating commodities is incredibly brittle. Complex, computerized supply-chains based on just-in-time production models have reduced the need for warehouses and depots. This often means that workplaces and retailers have less than a day’s reserves on hand, and rely on the constant arrival of new shipments. A few tactical interventions – at major ports, for instance – could bring an entire economy to its knees. This is obviously a problem for us as much as it is a problem for capital: the brittleness of the economy means that while it is easy for us to blockade the instruments of our own oppression, nowhere do we have access to the things that could replace it. There are few workplaces that we can take over and use to begin producing the things we need. We could take over the port and continue to import the things we need, but it’s nearly impossible to imagine doing so without maintaining the violence of the economy at present.

Power to the vagabonds and therefore to no class

This brings us to a very important aspect of the present moment, already touched on above. The subject of the “strike” is no longer the working class as such, though workers are always involved. The strike no longer appears only as the voluntary withdrawal of labor from a workplace by those employed there, but as the blockade, suppression (or even sabotage or destruction) of that workplace by proletarians who are alien to it, and perhaps to wage-labor entirely. We need to jettison our ideas about the “proper” subjects of the strike or class struggle. Though it is always preferable and sometimes necessary to gain workers’ support in order to shut down a particular workplace, it is not absolutely necessary, and we must admit that ideas about who has the right to strike or blockade a particular workplace are simply extensions of the law of property. If the historical general strikes involved the coordinated striking of large workplaces, around which “the masses,” including students, women who did unwaged housework, the unemployed and lumpenproletarians of the informal sector eventually gathered to form a generalized offensive against capital, here the causality is precisely reversed. It has gone curiously unremarked that the encampments of the Occupy movement, while claiming themselves the essential manifestations of some vast hypermajority – the 99% – are formed in large part from the ranks of the homeless and the jobless, even if a more demographically diverse group fills them out during rallies and marches. That a group like this – with few ties to organized labor – could call for and successfully organize a General Strike should tell us something about how different the world of 2011 is from that of 1946.

We find it helpful here to distinguish between the working class and the proletariat. Though many of us are both members of the working class and proletarians, these terms do not necessarily mean the same thing. The working class is defined by work, by the fact that it works. It is defined by the wage, on the one hand, and its capacity to produce value on the other. But the proletariat is defined by propertylessness. In Rome, proletarius was the name for someone who owned no property save his own offspring and himself, and frequently sold both into slavery as a result. Proletarians are those who are “without reserves” and therefore dependent upon the wage and capital. They have “nothing to sell except their own skins.” The important point to make here is that not all proletarians are working-class, since not all proletarians work for a wage. As the crisis of capitalism intensifies, such “wageless life” becomes more and more the norm. Of course, exploitation requires dispossession. These two terms name inextricable aspects of the conditions of life under the domination of capital, and even the proletarians who don’t work depend upon those who do, in direct and indirect ways.

The point, for us, is that certain struggles tend to emphasize one or the other of these aspects. Struggles that emphasize the fact of exploitation – its unfairness, its brutality – and seek to ameliorate the terms and character of labor in capitalism, take the working-class as their subject. On the other hand, struggles that emphasize dispossession and the very fact of class, seeking to abolish the difference between those who are “without reserves” and everyone else, take as their subject the proletariat as such. Because of the restructuring of the economy and weakness of labor, present-day struggles have no choice but to become proletarian struggles, however much they dress themselves up in the language and weaponry of a defeated working class. This is why the Occupy movement, even as much as it mumbles vaguely about the weakest of redistributionary measures – taxing the banks, for instance – refuses to issue any demands. There are no demands to make. Worker’s struggles these days tend to have few objects besides the preservation of jobs or the preservation of union contracts. They struggle to preserve the right to be exploited, the right to a wage, rather than for any expansion of pay and benefits. The power of the Occupy movement so far – despite the weakness of its discourse – is that it points in the direction of a proletarian struggle in which, instead of vainly petitioning the assorted rulers of the world, people begin to directly take the things they need to survive. Rather than an attempt to readjust the balance between the 99% and the 1%, such a struggle might be about people directly providing for themselves at a time when capital and the state can no longer provide for them.

Twilight of the unions