Filed under: Milwaukee area, update | Tags: anarchy, anti-capitalist, anti-state, books, burnt bookmobile, communism, discourse, distro, end, midwest, milwaukee

After almost 9 years of running a distro the Burnt Bookmobile no longer exists. Perhaps it will change name and form and resurface, with new intent and function. Where an absence is felt by this loss it is encouraged that others take on a similar project of circulating ideas, encouraging critical discourse, to find others (as many have through this project over the years) and to challenge and provoke each other to become ever powerful and potent in our lives and our thoughts, which are inseparable.

The website will remain up and archived as long as wordpress will let it.

If there are questions about how to start such a project please contact us at blowedupwisconsin at gmail dot com.

(perhaps something will be written that reflects more on the project rather than simply announcing its end in the near future.)

-Phantom Limbs of the Burnt Bookmobile

Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: CCC, cream city collectives, eviction, fuck landlords, fuck rent, halloween, milwaukee, october, party time

Only days after I left Milwaukee, the CCC got an eviction notice. I was overjoyed to hear that there was a proper eviction party, as all landlords deserve, but rarely get.

“On the evening of October 31st, hurricane Sandy swept through the space which once housed the Cream City Collectives. All of the former CCC’s windows were smashed by the winds and many beer cans were not picked up.

An accountability process for hurricane Sandy’s fucked up manarchist shit will be held at the next Twin Cities Anarchist Bookfair.

4 MORE YEARZ

4 MORE BEERZ

NO MOAR TEERZ”

http://incunabula.org/2012/11/hurricane-sandy-rips-through-milwaukee/

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anarchy, beginning, communism, indians, introduction, occupy, primitive, whitherburoo

“Thus in the midst of their greatest festivities, though physically thronging together, they live like wild beasts in a deep solitude of spirit and will, scarcely any two being able to agree since each follows his own pleasure and caprice. By reason of all this, providence decrees that, through obstinate factions and desperate civil wars, they shall turn their cities into forests and the forests into dens and lairs of men. . . Hence peoples who have reached this point of premeditated malice, when they receive this last remedy of providence and are thereby stunned and brutalized, are sensible no longer of comforts, delicacies, pleasures and pomp, but only of the sheer necessities of life. And the few survivors in the midst of an abundance of things necessary for life naturally become sociable, and, returning to the primitive simplicity of the first world of peoples, are again religious, truthful and faithful.”

-Vico, Scienza Nuova

Preface

1. It comes to pass, at last: this great Leviathan that has swallowed the whole world, now commences its death agony. The mechanical man likened unto the perfected State, with unweeping eyes and unfeeling heart, rusts from its own internal emptiness. The clockwork society breaks down. And the returning ghost towns, like a forgotten malediction, return to gaze mournfully at the passing of the glory of the world. The suburbs, this great gilded prison, agonize as they are left to return to nature, to slowly decay in their false-seeming gentility. The streetlights no longer illuminate the night on the edge of town, but cede way to their precursors, of which they are only the sad imitation, the moon and stars. The roads crumble into gravel, and from thence return to dust that they always were. Like unto like, America “is the nothingness that reduces itself to nothingness”, in the words of Hegel. Such are the heart-rending times the Americans inhabit.

This was the scenic backdrop of Occupy, which was not the beginning of anything new for America, as so many vulgar mediocrities would have us believe, but the faded repetition of its threadbare paltry ideals, and in truth, the pageant of the death agony of the American citizenry. The body politic will not revive: it is a corpse already beginning to putrefy. Who wants to be a part of death? There were those, with their prefabricated void collapsing of its own nullity, who wanted at all costs to stop this historically unprecedented implosion. They complained about rebuilding bridges, redistributing this or that. But look how intolerant their tolerance was: these liberals were openly working with the cops. Look how their spirits have so collapsed, these masterless slaves hate anyone acting manfully against the shameful degradation called American normality. And look how foolish these so-called educated are, who still believe they live in a democracy even while the police are throwing tear gas into their right to assembly, even while their beloved half-black puppet is currently giving the police the legal right to kill anyone. It is no great secret that America is terminally ill: it is clearly already braindead, its ever-feeble heart reduced to an automata of life support machines. One day, the de facto wards of this inhuman vegetable, the bankers and the military-industrial complex, will decide to pull the plug.

Before this predictable ignominious end, there was a message of hope, but not for the Stars and Stripes. The Occupy tents appeared in the heart of the grey steel cities, looking to the careful observer like a thousand Indian tipis had returned to the land they loved so dearly, exactly as they promised to do not so long ago. It had changed so much for the worse, but they still knew it as their own. It was as if they came back when Detroit and its productive apparatus lay shattered on the ground, when green shoots came into the crumbling brick and concrete buildings. When the long awaited wreck and ruin spoken of in the Ghost Dance was becoming so clear. When America was drowning in all the blood of the innocent it had spilled, and choking to death on all its ill-gotten plunder. The Indian spirits were completing their invisible revolution.

In these times, everything is progress towards the end. In America, all is progress towards the great collapse, the shriveling up and withering away of so much accumulated wickedness. Everyone contributes, willingly or no: the military and its totally failed, never-ending wars; the tea party cretins trying to refound their doomed American dream; a general culture spreading mindless saturnalian decadence, as before they danced in Rome even when the Empire was crumbling away; abused and neglected Mother Earth herself, and her beloved children, the ghosts of the Indians passed away in agony who haunt the dim-lit parking lots where nothing ever happens. . . everyone, in truth, longs for the collapse, because feeling and sentiment have retreated inside themselves to construct the world denied to them-all private life has become egoism and loneliness, an ornately gilded abyss. The public life of civic ideals no longer arouses even the scorn of laughter, so much has this passed into generalized derision with the growth of factional intrigues, conspiracies, crimes and murders. The American century is imploding, unmourned and unloved, from its own corruption and venality. Those who can still hear, let them hear.

Quality

2. The Americans have lived through a social movement, its ebb and flow, and now sit back and digest what they lived. They had forgotten their bodies, forgot the sting of tear gas and the feel of rocks in the pocket, a trusty stick in the hand, comrades all around. They had forgotten their bodies at the same time as history itself, because America is the most total alienation of humanity from itself.

To our eyes, the most remarkable thing, and most indicative of an alienation of intelligence from the mind, was the poverty of all hitherto-published analyses of Occupy. There was the predictable, hideous liberalism of Hedges and the rest of the peace police, that everyone knows only too well from the so-called antiwar movement. There was abstract graduate student Marxism, which only reflected the abstraction of their own lives. There was Crimethinc which now, having abandoned its previous lifestylism, has decided to become anarcho-insurrectionalist: the evidence of this turnabout is available to anyone who cares to read the back issues, or has some personal experience. But the same lack of principle is equally evident now: much like the spineless jellyfish that goes wherever the sea takes it, Crimethinc has now abandoned the anarchist identity of eating out of the garbage can for the anarchist identity of burning garbage cans. But that the latter is infinitely preferable to the former has nothing to do with an advance of Crimethinc, rather with the great sea tide of revolution of the past few years. One does not worry overmuch, as surely Crimethinc will be washed ashore and left to dry up in the sunshine of critique.

Various articles did remark on the incapacity of average people to connect America’s Occupy to its global contexts. They should have applied this critique to themselves, for how they failed to note how the global wave of revolts associated with Occupy- Cairo, Tunis, Madrid, Athens- were really only the globalization of American-style civil rights protests, and in our country that originated this type of civil rights protest, there was only a feeble imitation of elsewhere. Agamben was surely correct to see in Tiananmen the new face, the new type of revolt for the post-modern era. But it also means that America’s world-historic role to play, reducing everything to a nothingness of political debate, has ended. After all, in countries with more poverty, with more collective traditions, with less Protestant self-control, this same type of protest overthrows governments. At any rate, this means the end of a certain type of existence for the country itself.

What existence was there in America previously? It means very little to say, as the stock phrase would have it, that America was founded on slavery and genocide. So were many other countries. What matters is what is special about the American relation to their specific historical crimes? This, only a serious study of American history, and history in general, could give us. Unfortunately the so-called university intellectuals don’t spend their time reading, and what little they do is certainly not well-directed, just as so few monks at the end of the Middle Ages spent their time praying. Thus so few writers treated Occupy as a manifestation of the American phenomenon of Jacksonian Democracy as analyzed famously by De Tocqueville, or even further back to the troubles and arguments concerning the articles of confederation, the constitution, the period of the Alien and Sedition Acts, etc. To draw a line from these past moments, through the Civil War, the Populist and Progressive movements, to the New Deal, Civil Rights and 60′s, anti-globalization, and to Occupy, in short to treat Occupy in America as a specifically American moment, and Occupy globally as a moment of the globalization of American conditions, was lost on everyone. The growth of ideas of ideal citizen participation in a giant middle class system of representative democracy, with extreme energy but also reserve that rarely spills into violence, and never into revolution- this is the peculiarly American system. This is the system that worked, seemingly infallibly for a period, but now begins to collapse of its own perfection, like a towering house of cards that comes to put too much weight on its base. And in the gaps of the fallen cards new spaces of freedom appear.

Quantity

3.

But here was also remarkable: not only the feebleness of the previously existing reformist tension of the gigantic middle class, but the lack of any pretense at reform on the part of the politicians.

The Marxists, who only see the world in the night where all cows are black, have nothing to say to Americans other than the sad banalities they offer everywhere else. With this proviso, that here it is even a provincial and helpless variety. The Europeans can join Die Linke or Syriza, the American Marxists can offer only a ghostlike repetition of past failures, and an analysis of the economy in which no one believes anymore, and about which certainly no one cares. Moreover the Americans, with their fierce Protestant individuality, were never and could never have been attracted by Marxism. All the great heroes and traditions of American leftism are explicitly anarchist or anarchistic: Haymarket and May Day, the Wobblies, Sacco and Vanzetti, the Diggers and the counter-culture at large, the Battle of Seattle, the intellectuals of Bookchin, Chomsky, Graeber, etc.

The Americans are not even aware of their own history, perhaps even more so for radicals, and thus the turn of events of Occupy also makes no sense to them. Tom Hayden, in his excellent study The Love of Possession is a Disease With Them, remarked how when he visited the North Vietnamese, they knew more of America’s history than he did. They studied it as one studies an enemy from afar. How more greivous is the error when one does not study an enemy up close? The only branch of the workers’ movement that had some staying power, some cultural resonance and grounding in the U.S. was Anarchism, and that on the West Coast. Which is not to overstate the case: the French wrote that one cannot transpose Greek conditions to France, the land of the period of revolution from 1789 to 1871. How much more so would this be true for the Americans. Yet the Beat poets were aware, and wrote, that in some small way the wobbly spirit had survived to live on in the West. One might attribute this to the cultural dimensions of the restlessness of the frontier spirit, admirably captured by Frederick Jackson Turner, that, having reached the Pacific, turns inward against the newly constituted social order. The frontier only closed in 1890 with the Ghost Dance War, the wobblies were battling shortly thereafter. From thence to the struggles of the Depression, and the counterculture of the 60′s, then to the Battle of Seattle, the green anarchy movement and the student skirmishes of the past few years: only on the West Coast is there a tradition, however small, and only there is there the tiniest acceptance of political violence, as demonstrated in the refusal of Occupy Oakland to condemn property destruction. And if the complaint of the pointlessness of going to Oakland seems to have finally been taken into account on May Day, then so much the better. Berkeley and San Francisco offer better chances and targets, and it makes more sense for white revolutionaries to trash their own neighborhood rather than the visibly dilapidated and impoverished downtown of Oakland.

General analyses of America divide it roughly into a North, South, and West. The West has specific historical conditions that allow a form of Anarchism to exist there in some force, under its own banner. But not so elsewhere. Thus it is simply unreflective to demand that others emulate the West Coast in areas that are, effectively, separate countries, just as in Europe, Spaniards and Greeks can share aspirations as Mediterranean nations with a long history of extreme political violence, but the idea of transposing Greek tactics to Germany or Sweden, for example, makes absolutely no sense. We know from history the former two regions of North and South are so different as to have been separate countries at war for years. They are Sparta and Athens, one a landed aristocracy, the other a city-based democracy. Neither of the two have a tolerance for political violence; but the South for violence in general, yes, whereas for the North, not at all. The South is the bucolic countryside, the North is the urban sprawl of one contiguous ‘megalopolis’ from Boston to Washington. The South has Poe and Faulkner, terror and madness, the brooding over lost wealth; the North Thoreau, Whitman, the spirit of quaker pacifism, Anglophilism, and tolerance.

Finally the South deserves notice because it is the heart of America, America’s America of tiny towns and well-trimmed lawns, contentedness and civic pride. This is because it was the South that won the victories of the revolution, the planter aristocracy giving forth victorious Washington at Yorktown along with Jefferson and other theorists. After all, even the acts of treason to the Union in 1861 are constituted on the basis, the exact blueprint, of 1776, with the calling of state representatives to decide for independence and forming a new government. Hence the South is the cultural heart of America, and no wonder it gives such undue support to the Republican Party and the Army. However now Southern conditions are about to be generalized: only in the South has great wealth been lost in disastrous wars, and on the riverboats that the stock markets come to resemble more and more, and poverty nestled among American masses, and a universal reprobation met its abhorrent behavior. But now all of America has lost its war on terror, the money is drying up, and because of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, the general society all of America now deserves to be treated as was the South during Civil Rights, namely, as infamous and uncivilized. Agamben also writes that all societies go bankrupt in their own fashion: the Italians under Berlusconi, the Germans of 1933, etc. America has become spiritually bankrupt, much as MLK warned, and whenever this happens material bankruptcy is not far off in arriving.

Thus the real issue now posed to the Americans is: how to relate to the collapse? The U.S., the land of micro-fascism and molecular capitalism par excellence, is now evaporating, molecule by molecule. There is no austerity plan to protest against because the austerity is already being carried out in the hidden corners of the country. The small town library closes, the post office shuts up for good, the mayor’s office declares bankruptcy. Without as many police the people decide to police themselves, as we read for Vallejo, Ca. Americans are in a more revolutionary situation than they realize: they are in a situation like the end of Rome, where objectively a revolution should have happened long ago, but did not, and now the society is decaying and dying, like a butterfly too weak to shed its chrysalis: the last kernel of loyal citizenry has been wrecked by the War on Terror, they no longer believe in anything but suicide. Just read a newspaper. Graffiti is sprouting up everywhere. There is only a police force that everyone hates, and taxes and debt and no jobs. The society is collapsing in an orgy of its own violence: the violence that constituted the social fabric of the Americans, this blind bloodlust of Custer that so horrified the Indians, is now turning against the social fabric itself. The Hobbesian myth is becoming an unreal reality, for a time, before peace and contentedness return to this shattered, wounded, ancient land. But the Americans are lucky: whereas Rome collapsed into a foreign and inferior superstition of feeble-minded slaves and jaded aristocrats, the Americans fall back on what existed agelessly before their unhappy civilization. Indian simplicity, harmony with nature, collectivism, simple and unadorned love and devotion, guerrilla bravery. . .these are the things to remember. Americans don’t have to worry about a state to smash-they won’t even be at any comparable level of strength for years, they only just now begin a process of decades– they rather have to find something redeeming worth living, to save something from the final suicidal catastrophe of the American death culture.

Measure

4.

The whole new world opens up. Communism is first posed, abstractly, in a seeming plenitude: the life lived inside Occupy. Then the real world arrives with its numberless police, and even attempts to squat are dislodged. The question is of such utmost importance: where to nurture communism? It almost poses itself in the sense of Deleuze, of considerations of geophilosophy. If, on the West Coast, where the mountains descend to the sand and cliffs of the blue Pacific, the radicals go “up country”, as it was once called, they will still find old hippies in the countryside who will help them, who lived through the past era of revolution, and will find a life free from the expense and madness of the decaying American cities. In fact the expropriated farm at Berkeley offers the perfect bridge in its location at the end of the city, both to the countryside and to the past history of People’s Park, of American utopian experiments in general. The Americans have their own history of retreating to the land, that runs like a hidden current through their history. If Americans look hard at their own history they will find Utopia trying to emerge on the farm. Even in our general anglophone culture, Occupy the Land was the slogan of the original Diggers of the 1640′s. Or if the comrades in the Northeast go upstate, as happened previously at Oneida and with such stunning success at Woodstock, or even further to the tiny towns of Vermont, the land where Shays lived the rest of his life after his failed rebellion, and where Bookchin and his followers went. Perhaps those from the South can find something in the mountains of Kentucky and West Virginia, where John Brown planned to base his apocalyptic guerrilla war, and where the miners have struggled so fruitlessly, and for so long, against such odds. There is no great city to seize in America: just look at the wars with the British, they seized capital city after capital city, the Americans simply moved away. If there are only a few people in the countryside, there are only a few people in the cities worth talking to anyways: most of them are human wrecks of capitalism. If strategically and historically, space in America is almost flat, tending to zero, then go where no space exists: follow the heart, where it manifested in history, where kindness ends distance.

But the main point is to consolidate the gains of Occupy-these gains were very real, invisible only to historical materialists and skeptics- they were the friendships forged in prison and in the skirmish, the new world in the once-lonely hearts of millions of children of suburbia. Occupy, in its American context, means: the thawing of the glacial American sociality, on the route to its final evaporation. When Seattle was smashed again, the whole lost decade of the War on Terror is ended; the perspectives briefly glimpsed in the anti-globalization movement return, at a higher level. There are some days worth decades, and some decades worth days. The War on Terror decade had not the worth of one fine day in May.

In response, the police have begun to designate anarchists in general as public enemy number one. In fact, they are now to be treated as ‘the internal enemy’ of counter-insurgency theory. Thus, it is nowhere a question of repression, in the sad binary model of a power and a people. So many have read Foucault but so few have understood: what is at stake is not just repression but repression and then the creation of a subjectivity to be repressed apart from the general populace. There are no judicial questions (as even in the U.S. entrapment used to be not allowed as evidence before its terminal decadence) but military-strategical questions. The anarchists are to be presented as those trying to perform fantastic and disconnected acts of violence (which ironically will probably backfire and make anarchists even more beloved to all those who want the collapse, just as the majority of the world loved September 11). Even so, one cannot really count on a prevailing nihilism in American life to combat these strategies, as they are factors in play, not a strategy in itself. In fact rather than reaffirming whatever unimportant if not non-existent Anarchist identity existing America, as so many would be tempted to do (and here Crimethinc presents itself in its negative aspect, as the retarded consciousness of U.S. Anarchy in their latest anti-repression pamphlet), one would rather refuse this identity and merge into indistinction. In fact this idea has already been circulating amongst those repressed of the eco-anarchist movement about their aggressive veganism-puritanism, moralism, anti-humanism, etc. Thus it is clear to anyone that anarchists in general will be attacked the way the green anarchists were: but has no one even read what the prior generation of eco-radicals themselves have written? Certainly it’s not theoretical enough for the university Marxists, but other radicals have no excuse not to read what was written by those involved in the eco-scare cases. In any event, the question is not one of solidarity, which is unconditional, but on what basis and to what end. To try to free comrades, to not assume any political identity, or to affirm a feel-good label of extremism on the basis of a forthcoming political movement? A movement of American anarchism exists marginally, and only on the West coast because of cultural factors there: in a certain sense the Americans don’t have to go through the arduous process of evolution and internal critique of Greek Anarchy as documented in the excellent texts of flesh-machine, or rather, they shouldn’t. They don’t have to drive across the distance of a Siberia for a few days of tiny disturbances in a police state city, as in Chicago, or previously, any summit really. They can strike where there are, or go elsewhere for the duration. They don’t even have to wear black. Their extreme backwardness and weakness can become a blessing: they can fight oppression and build new lives without labels, as just humans.

Everyone asks, after the storms of battle, what next? We lost so many friends and lovers to the emptiness that we too, became loveless, and empty. But now there is a chance for building new buildings, for loving new lovers, for filling old emptiness, to end the wandering. In sum, Occupy, for the 1% of those who wanted to radicalize it, centers on resurrecting the counter-culture, with its urban space and its rural space, where anyone with a free heart could move like a fish in the sea. Now we, gasping fish dying of the outside world, have to cobble together our own new sea. Without the silliness, the drugs, the mysticism, the apathy. And this time, to last. Neither to rot in isolation nor to get lost in the normality of the American way of life after a rebellious youth. To escape from the life of student and barista, homeless and stay-at-home. Too many are rotting in the basements of their parental homes or at school. Provide the means for massive societal defection and it will surely come to pass-this is Grogan’s great lesson! In our lonely age of concrete, the guerrillas have to become farmers of the spirit, to plant the forest in which they will move. With the societal implosion, Americans will be forced into a new sociality, a new relationship with themselves and nature. It is already underway, with the market gardens of decaying suburbia springing up everywhere, and weeds and vines taking over the indifferent brick buildings. Those who read the signs, and act resolutely, will be all the better placed to profit from the generalized dissolution.

The Americans are only beginning to learn about sadness. When they have spent all the money and lost all the wars they will have only their own emptiness reflected back at them in their crumbling country with its abandoned factories and rotting monuments. . . but for the Indians, for all those who want the collapse, it is the beginning of the new life, it is the passing away of a world, the negation of the negation of the American way of life.

Escape. Rebuild the counter-culture, commune by commune. What care we of collapse, so long as we find one another? Let America and its glittering emptiness perish- we are for the Indians, we are for primitive, pure communism.

And we are beginning. .

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anti-police, blockade, miners, mines, spain, violence, work

Filed under: Milwaukee area | Tags: anarchy, bash back, CCC, cream city collectives, insurrectionary, milwaukee, queer, violence

This event is taking place at the CCC (732 E Clarke St.) at 7pm Thursday June 14th. It is free.

Queer Ultra Violence: Bash Back! Anthology published by Ardent Press this February, is an analytical anthology that chronicles the (non)organization and militant queer tendency known as Bash Back! Although short lived, Bash Back! had an astonishing impact on both radical and queer organizing in the United States. Bash Back! took on gay assimilation, anti-queer violence, the queer radical establishment, and capitalism with a queer struggle that rejected traditional identity politics. The anthology compiles essays, interviews, and communiqués to document the new queer tendency spawned by the Bash Back! years.

As capitalism and the state are thrown into deeper and deeper crisis, queers and all others historically excluded from both formal economies and from the safety net of the nuclear family, will bear the brunt of the age of austerity. Reflecting critically on the past several years of radical queer action and imagination, the editors of Bash Back! Queer Ultraviolence will attempt to navigate queer space and potential in a world torn by crisis. Through this talk, Eanelli and Baroque will present a series of proposals for action and survival, taking as their starting point the position of queer autonomy and queer revolt against the State and Capital. This lecture will theorize queer gangs, self-defense networks, occupations, communes and a praxis of vengeance.

http://www.ardentpress.org/bashback

Filed under: Milwaukee area | Tags: anti-capitalism, austerity, black bloc, crowds, elections, milwaukee, occupy, recall, rowdy crowds, scott walker

From AnarchistNews:

Four arrests Wednesday evening. A “keep it in the streets” protest in downtown Milwaukee followed the re-election of Governor Scott Walker, and was scheduled to respond to the victory of either politician. At this time, four have been released and cited with disorderly conduct and one more recently released back into our arms a day later than the rest. The five that were arrested were almost arbitrarily chosen for their close proximity to the blind and fevered panic of the police. The police, despite their smirks, had far less control over the situation than they want to say. At moments they had to put their hands on their guns just to convince themselves of who was in control. Shit was out of control.

After a year and a half being wasted on a recall election, after all of the energy put into the Capitol occupation and state-wide strikes was funneled into useless electoral politics, there is now room to breathe and begin again. This newfound freedom to act was seen in the streets of Milwaukee with surprising clarity. What started as a gathering of talking heads quickly escalated into a push and shove match with police, whose aim was to corner and stop any unpermitted march from taking place. Within seconds of the march, protesters took to the streets as dozens of cops in riot gear attempted to contain them. The crowd was unwilling to be pushed aside, and worked together to shove back and wind around the horses, motorcycles, and beefy baton-wielding helmets.

The black bloc, though dormant in Milwaukee for years, seemingly reappeared (some in all black, some with red bandannas, and some other groups and individuals who wore some form of the mask) and it both engaged in confrontation and helped to defend individuals in the crowd, while others that weren’t bloc’d up joined in and initiated their own actions. Its very presence declared non-violence an impossibility.

Police tried to stop the crowds, but failed again and again to contain its excesses. People pushed against police lines and horses and pulled their friends to safety as cops attempted to arrest them. One startled cop had some unknown liquid thrown at his face during the first attempted kettle. At another moment of police provocation a member of the crowd wrested a baton from the grip of a cavalry officer, hit him, and threw the baton at another, then jumped into the cloak of the crowd. It was unruly, disobedient, and willing to shove, at least 150 deep.

After twelve or so blocks of low-intensity conflict, protestors made it to Zeidler Park, the planned to be space of occupation. At this point the PA once again became an instrument of boredom as the crowd was talked at by people that wanted to give speeches instead of dance, or eat, or fight. Attention was then shifted to supporting those arrested, and a small crowd moved to the local police station to await their release. No occupation happened, but for now that is ok. All in all, the event was a short but inspiring leap away from the silly matter of a recall election.

When asked about the protest, police chief Flynn was quoted saying that it was MPD’s job to “babysit” the crowd while they “pretend to be relevant protestors”. We couldn’t disagree more. It is only now that the police have been identified as a thing to be fought, and the recognition that democracy will always fail to appease its audience that Wisconsin joins relevant contemporary struggle. Last year at the Capitol there was some confusion as to whether or not the police could be considered a part of the working class and it is very nice to see this question can put to rest. There is nothing more salient to present-day politics than an antagonism towards police.

Meanwhile, the media acted with calculation, minimizing and simplifying events, as they are expected to, creating a safe distance from any possible intensity. To them, it was simply a protest, it was “40”, it was “several”. It marched roughly half the actual distance down the forgettable avenue of Plankinton, when the wildness really cut through Water Street, the center of downtown. We blocked traffic “briefly” (ahem, forty god minutes at least). Their tendencies are to be non-descriptive, to imply that those that got arrested deserved it, and to minimize the actual event as much as possible, acknowledging it only so as to explain it away.

Similarly, the Left attempts to erase the excitement and power we experienced at the march. They talk about a peaceful, nonviolent protest where police officers unjustly arrested individuals to stifle free speech. From their press releases to the photos they post, the shining activists of the 99% were all but crushed, helpless victims.

The truth is that the march wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been as unruly and forceful as it had been, and there would have been many more arrests and injuries at the hands of the police. There was anger, and there was power.

To the rest of the world that is fighting and making 2012 the year that the world ends: Don’t wait for us, we’ll catch up!

We were not the 99%. We were 150, and we were angry.

Filed under: Milwaukee area | Tags: anti-capitalis, anti-walker, black bloc, conflict, elections, keep it in the streets, march, milwaukee, recall, wisconsin

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: active, bay of rage, debord, guy debord, la riots, oakland, passive, police, research and destroy, rodney king, spectacle, violence

From Bayofrage:

ϕ

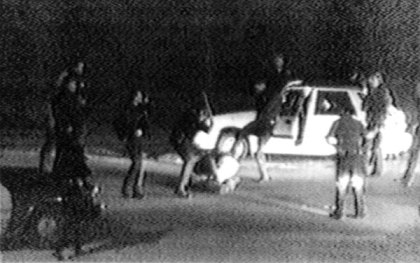

LOS ANGELES, March 3, 1991 – On the shoulder of the freeway, police are beating a man. Because we are in the US, and because the man is black, we will know that this is a routine event, an ordinary brutality, part of the very fabric of everyday life for non-whites. But something is exceptional this time. There is an observer, as there often is, but the observer holds in his hands an inhuman witness, a little device for producing images which are accepted as identical with the real. The images – grainy, shaking with the traces of the body behind them – enframe this event, defamiliarize it, make it appear in all its awfulness as both unimaginable singularity and example of a broader category of everyday violence. The recorded beating of Rodney King marks, as many have noted, the beginning of one of the most significant episodes of US history. But few have examined this event in terms of the transformative effects it exerted upon contemporary spectacle and its would-be enemies. By spectacle, we mean here those social relations and activities which are mediated directly by the representations, whether visual or verbal, which capital has subsumed (that is, remade according to its own imperatives).

For us, the advent of the Rodney King video marks the first major shift in the political economy of spectacle, which we choose to describe as a passage from passive to active spectacle, from spectacle as pacifying object of passive consumption to spectacle as the active product of the consumer (whose leisures or recreations have long since become forms of work). In its classical form, spectacle creates a situation in which “spectators are linked solely by their one-way relationship to the very center that keeps them isolated from each other” (Debord.) But at a certain point in its development, spectacle dispenses with the need for centralization, finding that passive consumers can quite easily be recruited to the production of spectacle. The shift from unilateral toward multilateral relations does not promise an end to isolation, but rather its perfection. We might think of the distinction here as the difference between the television screen and the computer screen, but since we are talking about a set of social relations as much as technological apparatuses, we should be careful to avoid identifying such relations with any particular technologies. The video camera is merely one of many devices which assist in the transformation of administered life into self-administered life.

But back to the origin story (like all origin stories, it’s partly myth). The mutation from passive to active spectacle begins, as seems properly literary, square in the middle of one of the most significant nerve-plexuses of the spectacular world: Rodney King is beaten to the edge of death a few miles from the studios of Burbank and Hollywood, while celebrities whizz by in Porsches and Maseratis. A routine event, an ordinary brutality, an everyday violence: a black man is pulled over by white police officers. They have some reason or another. There is always a reason, if only raison d’État. They beat King savagely, until he is almost dead. Perhaps they have gone a little too far this time, gotten a little overexcited? In any case, it’s nothing that can’t be taken care of, made to disappear with a few obfuscatory phrases in the police report. Except that, somehow, everything is different here. Recorded, duplicated, transmitted, broken down into the pixels of a million television screens, the video tape is more than evidence. It is self-evidence. And because these images are drained of all affect, reduced to pure objectivity, they can become the vehicle for the most violent and intense of affects.

ϕ

The release of this video marks, more or less, the entrance into history of the video camera as weapon, as instrument of counter-surveillance. For a brief moment it does seem, for many, as if the truth really will set us free. As if the problem with capitalism was that people just didn’t know, just didn’t understand, just hadn’t seen what it’s really like underneath the ideological mist. Noam Chomsky’s politics as much as Julian Assange’s seem to hinge upon this kind of moment – so rare, really – when the release of information becomes explosive, as opposed to the thousands of other moments when the leaked photographs of government torture camps or the public records dump indicating widespread fraud and corruption fail to elicit any outrage whatsoever. From here and from the related forms of media activism which the Rodney King tape precipitates, there flows an entire politics of transparency, based on a correlation between the free circulation of information and freedom as such, which we will recognize as the politics of Wikileaks and the more-libertarian wing of Anonymous. But this is also the matrix from which emerges the ideology of the Twitter hashtag and the livestreamed video that so animates the Occupy movement and the 15 May movement in Spain, an ideology that seems incapable of distinguishing between OWS and #ows, between the massification of “tweets” around a particular theme and the massing of bodies together in an occupied square. As many of us will know from the experience of the last year, this is an ideology that speaks of democracy but reeks of surveillance, whose wish for a world transparent to all means that it sees a provocateur behind every masked face and unassailable virtue in all that is visible and unmasked.

ϕ

But we have already skipped to the end, it seems, far from the infancy of active spectacle. At first, it’s true, the mass media display a certain hostility to these newer “participatory” forms of media distribution and production, which seem to threaten the centralized, unidirectional spectacle upon which the mass media are built. The various conglomerates even resort to outright repression on occasion. But from the very beginning it is startlingly clear that recuperation and neutralization are a far easier path. Take the industry of “news reporting,” for instance. As the cable channels shift over to 24/7 reporting, it is no longer sufficient to pursue the old spectacular schemata, creating, rather than merely reporting on, the various scandals and sensations. It is not enough to simply position the cameras in a certain spot and observe their effect on the filmed. The news must become co-extensive with the time of life itself. One must, therefore, do more than simply create novelties. In the era of active spectacle, one must create the proper conditions for the novel and newsworthy. But, as we know, the news has been manufactured to produce certain effects since long before the appearance of active spectacle. Reporters rarely pursue their prey, as one is led to believe. Instead, the reported-on must actively solicit coverage, since the various agencies will rarely venture out into the wild of lived experience. Why would they need to, when so much material is already manufactured to their specifications by corporations and governmental entities? Therefore, the periodization described above must be complicated a bit. The transformation that emerges with the video camera and social media is really a generalization of the capacity to produce the true which was, during the classical era of spectacle, limited to certain elites. Active spectacle was, in its way, always nascent within passive spectacle. You just had to pay more for its privileges.

ϕ

Every scandal loves a trial. And this is the age, let’s remember, of the blockbuster trial, the totally televised trial, followed droolingly by the recently developed 24/7 cable news channels still looking for content to fill out the hours. The 1990s: one could tell its story solely through the names King, Simpson, Clinton. And so the trial of the police officers begins, a trial that puts at stake the institution of the police itself, if only because the state must insist, in defending the officers, that their conduct was merely exemplary, that they were simply doing their job. But it is a trial in another sense, an experiment with a new form of publicity and sensationalism that places the courtroom square in the middle of every living room: it is a putting-on-trial of a new kind of reason, a new affect, and the various powers are reckless here in stoking a paranoid desire for apocalyptic violence. (Later, they will understand their own capacities better, and exhibit more circumspection in deploying such powers in unpredictable environments).

No one, therefore, is really all that surprised when – after the police officers who beat Rodney King are pronounced not guilty – thousands upon thousands of the invisible residents of this hypervisible city rise up to smash and burn and loot the very machinery which determines who gets seen and how. In this sense, the Los Angeles riots of 1992 are a rare example of a struggle over the terms of representation which is not a diversion from struggle on the material plane but rather an incitement to it, perhaps because this is not a struggle for representation as much as it is a struggle against representation, one that puts into question the very means of deciding what gets seen or said, rather than the content of such seeing or saying. For a few nights, it promises the self-destruction of all our ways of making things visible or heard, a bonfire of the means of depicting and speaking which the most adventurous avant-garde could only dream about.

As noted, none of this controverts the extent to which these were bread riots, or their late 20th-century equivalent – organized, as is the case with all looting, around a material expropriation of necessaries and luxuries alike. But perhaps, more importantly, crystallized around the hatred of commodities, a hatred whose satisfaction means, in fact, the slaking of a thirst almost as urgent as the need for the use-values themselves. We have to understand this as a period of outright war, when the number of people – black men, in particular – serving prison sentences increased by an order of magnitude, when cops were being trained by Special Forces who brought the “lessons” of the Central American counter-insurgency wars home to South Central Los Angeles. Which is to say that these were matters of life and death as well as recognition – closer to the original Hegelian story of life-and-death struggle for recognition than its pale electoral successors . One must see people stealing the video-cameras and televisions – the big-ticket appliances of which they bad been, for so long, the object – as an attempt to secure their very reality. To become subject, not object. Spectacle, for a brief moment, reveals its own fragility: transmitting, disseminating and relaying antagonism rather than muting and deflecting it. For a moment, self-representation is not the newest face of domination, an internalization of the enemy, but promises the destruction of all mediation, all intermediaries. Bill Cosby goes on TV to urge the rioters to return to their homes and watch the season finale of The Cosby Show.

In a certain manner, this project of expropriating the means of representation and transmission is an eloquent literalization of the music of the riots itself, hip hop, a music based upon the transformation of consumer electronics – the turntable, the home stereo – into instruments of musical production. Technologies which were once means of production – capital goods, in other words – become consumer products. But then, in a final turn, these consumer products become, once again, the means of production for a new generation of untrained musicians whose output is based upon appropriation and sampling, which are a particular kind of consumption-become-production. All the dreams of decentralization and horizontality which we will fondly remember in their suffusion through the 1990s begin here: the politics of the rhizome, the network, the galaxy, the autonomous nuclei. They begin here, with mass-produced consumer electronics whose drive is not only toward cheapening but miniaturization. It’s not just that information wants to be free; it wants to become a kind of gas, an array of volatilized nano-machines, circumambient, hyperlocative. “Copwatch” organizations and other counter-surveillance projects – taking the Rodney King video as their clarion call – spread faster and farther as the price of the camcorder falls, as it becomes smaller, lighter. They spread at the same rate as CCTV spreads, adorning every street corner in cities like Chicago and London. And, of course, tactical representation finds itself eminently suited to the politics of representation that dominates the liberal multiculturalism of the 1990s. An entire ethos is built upon this pedagogical and epistemological basis. Information and its dissemination becomes the means by which everyone can have their voice. The independent media initiatives that emerge at the end of the decade essentially elaborate upon this foundation: the free circulation of information as a placeholder for other freedoms.

In Los Angeles during the 1990s, this made a certain sense. We will render power visible, we thought. We will show everyone that the emperor has no clothes. We will show everyone who they are. Like the sunglasses in John Carpenter’s They Live, capable of revealing the slithering horror beneath the familiar present which our normal (that is, ideological) vision construes – the camcorder would disclose what others couldn’t see. It would be visceral and immediate in a way that language cannot, even if language is capable of making finer distinctions. But it would also make things seem unreal. It would also be an instrument of de-realization, shifting struggle from the ground of praxis toward the ground of epistemology, and from there toward questions of knowledge and ideology which, presumably, only the technicians of politics can solve for us. And so, in the wake of the riots, the recuperation begins. Like all recuperations, it will seem to precede, somehow, the acts of resistance from which it sprang, if only by erasing their real origin.

ϕ

The shift from static, passive spectacle to dynamic, active spectacle is nothing other than this process of recuperation and subsumption. Charged with reproducing the social relations necessary for the continuation of capitalism, spectacle adjusts to its critique, subsumes it, offers up a series of false alternatives decorated in the bracing negativity of the day. Spectacle stages its own negation, the way a hunted criminal might stage her own death by leaving behind someone else’s corpse in place of her own. Spectacle in its classical phase proceeded by replacing all exchanges between persons with dead phrases and images subject to the whims of the commodity, with static and chatter designed to baffle and delay any intelligent action. It thwarted any meaningful activity by all manner of phantasms, false leads, cul-de-sacs and proxies. But its weakness was that it required the constant ministrations of a class of petit-bourgeois intermediaries, clericals, creatives and technicians, themselves the group most deeply colonized by spectacle. Active spectacle, on the other hand, does away with some portion of this class. Active spectacle is, first and foremost, a labor-saving device. It is a way of getting the consumer of spectacle to become the producer of spectacle, all the while pretending that this voluntary labor is, in fact, a form of freedom and greater choice, an escape from the stultifying imposition of this or that taste which the vertical power of the passive spectacle forces on us.

This is an alternate way to talk about the recuperation of negativity which has been ongoing since the 1970s. Everyone is familiar with this – the graffiti kids who add value to a neighborhood by fucking it up, giving it the right degree of color and edginess, and perhaps inspiring, with their visual style, some future generation of designers and advertisers. Eventually, as we all know, the great spread of alternative lifestyles and forms and subcultures that follow in the wake of the aborted liberations of the 1960s and 1970s find their final resting place in the boutique or the museum, and this process – let’s call it the turnover time of recuperation – is constantly accelerating. But the paradigmatic case here, the final profusion, comes in the realm of technology: the merger of home and office, work and leisure, effected by the personal computer means that one finally becomes the consumer of one’s own self-designed fantasias. These are tools for taking the dream of autonomy concealed in the notion of self-management and converting it into an efficient machine for exploitation and control – a way of making the cop and the boss immanent to our every activity. The miniaturization of information technology – which also means the recession and involution of all its working components, so that the surface can be humanized, made aesthetically pleasing – allows for control to be decentralized, networked, built from the ground up in new shapes and flavors. It is a way of spreading the bureaucratic protocols of office technology across the entirety of society.

Once the internet is streamlined, cheapened, and made easy-to-use, an entire political ontology gets attached to “the net”– its origin in military-industrial and bureaucratic protocols hidden beneath warm, “user-friendly” layers which promise the end of a merely unilateral media, promise a new media based upon participation, self-actualization, democracy, promise to free us from reliance upon authoritarian or hierarchical communication. It is a media, as many will claim, which encourages dissent rather than suppresses it, a media no longer dependent upon the massifications and conformities of the broadcast form. No longer the passive receiver of consumable representations, we become the co-creators of the conditions of our own subordination – we don’t merely choose from the 1001 flavors of horror on offer but actively create them, share them, use them as the basic substance of our connections to others, whether friend, enemy, or acquaintance. We are free to make and remake ourselves endlessly in the shape of a thousand avatars and personae. Never mind that these technologies depend, at root, upon standardized lumps of silica and copper and plastic, on the smoothing of electrical switches into reified patterns and routines, on the transformation of matter into algebra. For the various “independent media” initiatives, the internet is as fundamental an apparatus as the video-camera was for the copwatch programs.

The advent of blogging and the various social networking sites – MySpace, then Facebook, and finally (once everyone realized that anything worth saying in such fora could be said in 140 characters or not at all) Twitter – essentially build upon the protocols, models and values established by “independent media.” They represent the depoliticization of these forms, something easy to do since, from the start, “indymedia” as a concept was built around a false formalism. Because the website proved itself such an effective tool for the coordination of thousands of bodies at the counter-summit – distributing information about the location of rioting, tactical weaknesses, arrestees, food and medical services – it was obvious that it could also serve to coordinate thousands of bodies in other kinds of campaigns: advertising campaigns, fundraising drives, mobilizations for this or that political candidate. Social media: the term means that our sociality itself has become what is communicated, has become content, not form. No longer do we merely read the news: now we can write it, now we can make it even more banal and empty than before. Yes, everyone their 15 minutes of celebrity, except now these 15 minutes are broken up into millisecond-sized atoms of time, salted throughout our hours and days, held by invisible readers and contacts and “friends.” Here the voyeur meets the exhibitionist. Here the exhibitionist meets the voyeur. Here the most gregarious sociality and the most contorted narcissism are absolutely identical. Tellingly, new cellular phones now contain two cameras – one facing out into the world, away from the screen, and one reflecting back upon the ego.

But because active spectacle takes hostility toward spectacle as one of its primary fuel sources, because it is always cultivating such antagonism at the same time as it neutralizes it, there is always the possibility of explosive breakdown, the possibility that a violent proletarian content may become contagious. Such was the case when the WikiLeaks affair – initially subsumed almost completely by a libertarian logic of transparency and the free flow of information – transformed into a low-intensity cyberwar with the arrival of Anonymous, LulzSec and others. Although originally entirely devoted to a kind of Assangiste framework that cared only about the free flow of internet information (namely, porn, pirated media and software) – a position that still dominates much of their discourse – these groups eventually became frameworks into which more and more radical content could get injected, and now one routinely hears Anonymous communiqués cite various insurrectionary watchwords, and describe their enemy not as censorship but capitalism and the state as such. Perhaps more significantly, we can note the way in which technologies like Twitter – originally developed so that we could better market commodities to each other – are now used for all-out assaults on the commodity, used to organize proletarian flashmobs and rioting in the suburbs of London, in Baltimore and Kansas City and Milwaukee.

ϕ

10 years later, we all recognize the limits of the anti-globalization movement, limits that still constantly reimpose themselves even if we have moved into a new age of austerity and riot. The antiglobalization movement failed by winning all that it won on the ground of representation alone. Not only were its politics essentially a representational critique of the representational (direct democracy); not only did it fight via representational means (media activism); but more importantly its focus remained limited to the representatives of multi-national capital: the institutions and ambassadors responsible for maintaining the international monetary and trade system. Over and over again, the countersummit conflated the representative institutions for the thing itself – moving back and forth between an attack on a proxy for capital, and capital itself.

It is obvious that this imprisonment within the imaginary is an effect of the very basis – a technopolitical basis – upon which these struggles are conducted, rather than the other way around. Representation is means, content and form: everyone has a camera at the protest and the dangers here are not only that one is unwittingly capturing evidence for the state, but that we are therefore entrapped within the imaginary, our finest moments rendered pornographic – that is, made into a simple conduit for charge or sensation, upon which any idea, no matter how fascist, can be overlaid.

Let’s put it bluntly: with only a few exceptions, the journalists whose presence at the demonstration or riot is vouchsafed by the camera are nothing other than the agents of the state, little different than informants in their attitude toward what transpires. Their feigned neutrality is the neutrality of “the citizen,” of public opinion, an enemy position. Except when used with incredible care and sensitivity and artfulness, the camera is basically an instrument of neutralization. We can have no tolerance for those who attempt to use our antagonism as stepping-stones in their career; nor can we tolerate the special rights and privileges which journalists want to claim, as if holding a camera or press-badge entitled them to exceptional status. This is liberalism’s phantasm – the materialization of the abstract personhood which has mangled our lives for centuries. In any case, the police no longer give a fuck. Everywhere there are new laws prohibiting the filming of police and they now routinely arrest people because they have a camera, not only to protect themselves from scandal but to collect evidence.

ϕ

Surveillance and countersurveillance, spectacle and counterspectacle, then, merge together into one representational surround. Riot footage becomes an advertisement for jeans, as if shopping and destroying a shop were equivalent activities. If counter-surveillance aims to light up the unevenesses, the blotches and stains that the picture of the world hides, it also runs the risk, as all struggles do, of fighting on the ground of representation alone, and of winning thusly the mere representation of winning. Though we do not use the term in this sense exclusively, this is what it means to speak of “politics” in the pejorative sense – the translation of struggle to the realm of representation, either through the substitutionism of the assembly, the party, or the image-world. It means to fight representatives and proxies endlessly and pyrrhically, because capital is nothing more than this process of creating proxies. The catch is that, because they still believe that the question of representation is the question that must be answered, many anti-representational strategies – the participatory democracy of the general assembly, for instance – remain trapped within politics in the same way that the atheist remains trapped within religion because he or she takes seriously the question of god’s existence.

ϕ

The one exception to this story of diversion to the ground of representation is the black bloc, which by its very nature refuses visibility. The black bloc emerges as a counterweight to the regime of hypervisibilty, emerges as the avenging angel of all that has been cast into the burning hell of the overlit world. It conjures a black spot which makes the illumination of the world all the more severe; it is a kind of “darkness visible,” as Milton says of Lucifer’s resting place. But at what point does this darkness become only its own visibility, a set of predictable movements and moments, easily recognized simply because it is the thing which refuses recognition? How often is it the case that the plate glass of the bank is shattered but the camera lens, with all of its frightening transparency, remains? One of the problems, here, as others have noted, is that the black bloc often distinguishes itself from the larger mass of people in the streets. Even if all identity inside the group is quickly liquidated by masks and black clothing, the bloc still affirms an identity – albeit a negative one – with regard to its environment. Rather than attempting an absolute negation of visibility, we might instead cultivate a kind of chiaroscuro effect, attending to the ebb and flow of light and shadow naturally at play in such situations. True anonymity is the anonymity of the crowd, the anonymity of people in regular dress who begin to throw rocks at cops, loot stores, and burn cars, and whose anonymity comes from their subtle commonalities with thousands upon thousands of other figures. (Though, of course, concealing one’s face is a precaution that can never be dispensed with, and should be actively encouraged on all occasions). The more it becomes possible for the active minority to merge with the anonymous crowd, to dissolve and abolish its own specificity at the height of the attack, the closer we come to the kind of riot which continues past the first night. Whether people continue to use black blocs is a practical matter, of course, and has to do with local conditions which cannot be evaluated in the abstract. But we must be honest about the limitations of the form, and note that there are anonymities superior to the black bloc, forms of self-abolition that do not establish a radical identity apart from the larger mass of people in the streets.

It is not, therefore, merely a question of creating “zones of offensive opacity.” Every opacity has its complementary transparency, and we must attend to both. We must be willing to make ourselves visible here, invisible there, and neither everywhere. Language, in this sense, is often superior to the photograph’s ontological trickery. We all recognize the power of the well-written communiqué or manifesto, the well-designed poster with the explosive phrase. This power is art, poetry, art that lives on, nevertheless, after the death of art. Taken up on the field of battle, conjoined with real practices of negation, this poetry – the beautiful language of our century, as it was once called – has a real explosive force, one that does not pass through reason and understanding alone, but which trades on affect, perception, sensation. The technical means we have at present for conveying such affects and perceptions are, let’s admit it, very weak – a series of pre-given filters and plug-ins which we can apply to this or that image or idea. Why is it, then, that the various radical milieus do not at present produce more films, more poetry and novels, communicate through drawings and illustrated stories as well as photographs? Why must we subordinate ourselves to a barren plain-style, on the one hand, and a mawkish sentimentalism on the other? Why do we accept the self-evidence of the very images which the state uses to speak about us? In expanding our capacities for thought and communication, in expanding the formal and technical means for such, we must learn to speak of and to each other in a way that takes exception with the way we are spoken about, which takes exception with the language of the status quo, the state. This is a matter of how we say such things as much as what we say. Active spectacle, let’s remember, hides the issue of content by allowing for modest transformations of the form of communication. This is why the transposition of the locus of questioning from what to how relies on a weak understanding of recent history. Asking how has, for a long time now, been a counter-revolutionary question.

ϕ

Late in life, in the midst of his drunken melancholia and paranoid rumination, Guy Debord entertained himself by inventing a chess-like game of war in which the chief innovation was the establishment of lines of communication between pieces. Pieces that were unconnected via intermediating, communicating pieces could not move at all. Debord understood, in this game as well as in his writing, that all struggles have a communicative dimension. The difference, however, between the situation we confront and the situation in Debord’s game is that we are forced to use the very same lines of communication as our enemy. Every one of our communications is at one and the same time an enemy transmission, part of the enemy system, part of spectacle. To operate effectively, to turn spectacle in its active form against itself, we have to examine our communications both from our own standpoint and the enemy’s, developing forms of communication which are transparent for us but opaque for them, which allow us to communicate and expand our ability to think and perceive collectively without assisting the state in its attempts to monitor and obstruct us, and which reach out to sympathizers, fellow-travelers, and comrades without giving away vital information to the enemy.

In this regard, matters of style are at one and the same time matters of survival.

ϕ

Research & Destroy

Oakland, CA

April, 2012

Filed under: war-machine | Tags: anti-capitalism, death, decomposition, may day, oakland, oakland commune, Occupy oakland, occupy wall street

From Bayofrage:

May 1, decomposition and the coming antagonisms

THE COMMUNE

For those of us in Oakland, “Occupy Wall Street” was always a strange fit. While much of the country sat eerily quiet in the years before the Hot Fall of 2011, a unique rebelliousness that regularly erupted in militant antagonisms with the police was already taking root in the streets of the Bay. From numerous anti-police riots triggered by the execution of Oscar Grant on New Year’s Day 2009, to the wave of anti-austerity student occupations in late 2009 and early 2010, to the native protest encampment at Glen Cove in 2011, to the the sequence of Anonymous BART disruptions in the month before Occupy Wall Street kicked off, our greater metropolitan area re-emerged in recent years as a primary hub of struggle in this country. The intersection at 14th and Broadway in downtown Oakland was, more often than not, “ground zero” for these conflicts.

If we had chosen to follow the specific trajectory prescribed by Adbusters and the Zucotti-based organizers of Occupy Wall Street, we would have staked out our local Occupy camp somewhere in the heart of the capitol of West Coast capital, as a beachhead in the enemy territory of San Francisco’s financial district. Some did this early on, following in the footsteps of the growing list of other encampments scattered across the country like a colorful but confused archipelago of anti-financial indignation. According to this logic, it would make no sense for the epicenter of the movement to emerge in a medium sized, proletarian city on the other side of the bay.

We intentionally chose a different path based on a longer trajectory and rooted in a set of shared experiences that emerged directly from recent struggles. Vague populist slogans about the 99%, savvy use of social networking, shady figures running around in Guy Fawkes masks, none of this played any kind of significant role in bringing us to the forefront of the Occupy movement. In the rebel town of Oakland, we built a camp that was not so much the emergence of a new social movement, but the unprecedented convergence of preexisting local movements and antagonistic tendencies all looking for a fight with capital and the state while learning to take care of each other and our city in the most radical ways possible.

This is what we began to call The Oakland Commune; that dense network of new found affinity and rebelliousness that sliced through seemingly impenetrable social barriers like never before. Our “war machine and our care machine” as one comrade put it. No cops, no politicians, plenty of “autonomous actions”; the Commune materialized for one month in liberated Oscar Grant Plaza at the corner of 14th & Broadway. Here we fed each other, lived together and began to learn how to actually care for one another while launching unmediated assaults on our enemies: local government, the downtown business elite and transnational capital. These attacks culminated with the General Strike of November 2 and subsequent West Coast Port Blockade.

In their repeated attacks on Occupy Oakland, the local decolonize tendency is in some ways correct.[1] Occupy Wall Street and the movement of the 99% become very problematic when applied to a city such as Oakland and reek of white liberal politics imposed from afar on a diverse population already living under brutal police occupation. What our decolonizing comrades fail to grasp (intentionally or not) is that the rebellion which unfolded in front of City Hall in Oscar Grant Plaza does not trace its roots back to September 17, 2011 when thousands of 99%ers marched through Wall Street and set up camp in Lower Manhattan. The Oakland Commune was born much earlier on January 7, 2009 when those youngsters climbed on top of an OPD cruiser and started kicking in the windshield to the cheers of the crowd. Thus the name of the Commune’s temporarily reclaimed space where anti-capitalist processes of decolonization were unleashed: Oscar Grant Plaza.

Why then did it take nearly three years for the Commune to finally come out into the open and begin to unveil its true potential? Maybe it needed time to grow quietly, celebrating the small victories and nursing itself back to health after bitter defeats such as the depressing end of the student movement on March 4, 2010. Or maybe it needed to see its own reflection in Tahrir, Plaza del Sol and Syntagma before having the confidence to brazenly declare war on the entire capitalist order. One thing is for sure. Regardless of Occupy Wall Street’s shortcomings and the reformist tendencies that latched on to the movement of the 99%, the fact that some kind of open revolt was rapidly spreading like a virus across the rest of the country is what gave us the political space in Oakland to realize our rebel dreams. This point cannot be overemphasized. We are strongest when we are not alone. We will be isolated and crushed if Oakland is contained as some militant outlier while the rest of the country sits quiet and our comrades in other cities are content consuming riot porn emerging from our streets while cheering us on and occasionally coming to visit, hoping to get their small piece of the action.

THE MOVEMENT

For a whole generation of young people in this country, these past six months have been the first taste of what it means to struggle as part of a multiplying and complex social movement that continually expands the realm of possibilities and pushes participants through radicalization processes that normally take years. The closest recent equivalent is probably the first (and most vibrant) wave of North American anti-globalization mobilizations from late 1999 through the first half of 2001. This movement also brought a wide range of tendencies together under a reformist banner of “Fair Trade” & “Global Justice” while simultaneously pointing towards a systemic critique of global capitalism and a militant street politics of disruption.

The similarities end there and this break with the past is what Occupy got right. Looking back over those heady days at the turn of the millennia (or the waves of summit hopping that followed), the moments of actually living in struggle and experiencing rupture in front of one’s eyes were few and far between. They usually unfolded during a mass mobilization in the middle of one “National Security Event” or another in some city on the other side of the country (or world!). The affinities developed during that time were invaluable, but cannot compare to the seeds of resistance that were sown simultaneously in hundreds of urban areas this past Fall.

It makes no sense to overly fetishize the tactic of occupations, no more than it does to limiting resistance exclusively to blockades or clandestine attacks. Yet the widespread emergence of public occupations qualitatively changed what it means to resist. For contemporary American social movements, it is something new to liberate space that is normally policed to keep the city functioning smoothly as a wealth generating machine and transform it into a node of struggle and rebellion. To do this day after day, rooted in the the city where you live and strengthening connections with neighbors and comrades, is a first taste of what it truly means to have a life worth living. For those few months in the fall, American cities took on new geographies of the movement’s making and rebels began to sketch out maps of coming insurrections and revolts.

This was the climate that the Oakland Commune blossomed within. In those places and moments where Occupy Wall Street embodied these characteristics as opposed to the reformist tendencies of the 99%’s nonviolent campaign to fix capitalism, the movement itself was a beautiful thing. Little communes came to life in cities and towns near and far. Those days have now passed but the consequences of millions having felt that solidarity, power and freedom will have long lasting and extreme consequences.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the movement is now decomposing and that we are now, more or less, alone, passing that empty park or plaza on the way to work (or looking for work) which seemed only yesterday so loud and colorful and full of possibilities.

All of the large social movements in this country following the anti-globalization period have heated up quickly, bringing in millions before being crushed or co-opted equally as quickly. The anti-war movement brought millions out in mass marches in the months before bombs began falling over Baghdad but was quickly co-opted into an “Anybody but Bush” campaign just in time for the 2004 election cycle. The immigrant rights movement exploded during the spring of 2006, successfully stopping the repressive and racist HR4437 legislation by organizing the largest protest in US history (and arguably the closest thing we have ever seen to a nation-wide general strike) on May 1 of that year [2]. The movement was quickly scared off the streets by a brutal wave of ICE raids and deportations that continue to this day. Closer to home, the anti-austerity movement that swept through California campuses in late 2009 escalated rapidly during the fall through combative building occupations across the state. But by March 4, 2010, the movement had been successfully split apart by repressing the militant tendencies and trapping the more moderate ones in an impotent campaign to lobby elected officials in Sacramento. Such is the rapid cycle of mobilization and decomposition for social movements in late capitalist America.

THE DECOMPOSITION

So what then killed Occupy? The 99%ers and reactionary liberals will quickly point to those of us in Oakland and our counterparts in other cites who wave the black flag as having alienated the masses with our “Black Bloc Tactics” and extremist views on the police and the economy. Many militants will just as quickly blame the sinister forces of co-optation, whether they be the trade union bureaucrats, the 99% Spring nonviolence training seminars or the array of pacifying social justice non-profits. Both of these positions fundamentally miss the underlying dynamic that has been the determining factor in the outcome thus far: all of the camps were evicted by the cops. Every single one.

All of those liberated spaces where rebellious relationships, ideas and actions could proliferate were bulldozed like so many shanty towns across the world that stand in the way of airports, highways and Olympic arenas. The sad reality is that we are not getting those camps back. Not after power saw the contagious militancy spreading from Oakland and other points of conflict on the Occupy map and realized what a threat all those tents and card board signs and discussions late into the night could potentially become.

No matter how different Occupy Oakland was from the rest of Occupy Wall Street, its life and death were intimately connected with the health of the broader movement. Once the camps were evicted, the other major defining feature of Occupy, the general assemblies, were left without an anchor and have since floated into irrelevance as hollow decision making bodies that represent no one and are more concerned with their own reproduction than anything else. There have been a wide range of attempts here in Oakland at illuminating a path forward into the next phase of the movement. These include foreclosure defense, the port blockades, linking up with rank and file labor to fight bosses in a variety of sectors, clandestine squatting and even neighborhood BBQs. All of these are interesting directions and have potential. Yet without being connected to the vortex of a communal occupation, they become isolated activist campaigns. None of them can replace the essential role of weaving together a rebel social fabric of affinity and camaraderie that only the camps have been able to play thus far.